WILLOWBROOK CHANGED HOW STATE TREATS PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

Attica. Love Canal. Willowbrook.

Their mere mention conjures stomach-turning images of bloodshed, contamination and people with disabilities lying in their own excrement.

These three New York disasters from the 1970s also evoke memories of scandal, failure and shame. They forever changed how New York State treats the incarcerated, the environment, and people with disabilities.

The 1971 inmate uprising at Attica, which left 43 dead, led to “a near total overhaul of the state’s corrections and prison policy,” as reported by the Plattsburgh Press-Republican.

Love Canal led to creation of the federal Superfund program and exemplified the power of local environmental activism, driven by moms, and the start of the “environmental justice” movement.

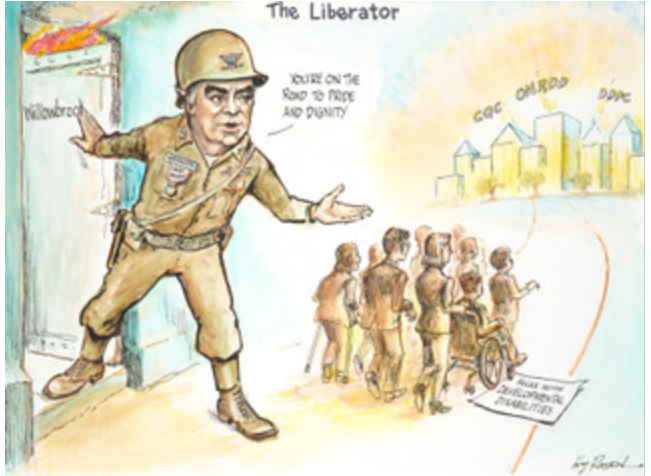

Willowbrook might be the most graphic of the three because of the way it was captured by TV news cameras. Designed for 4,000, the Staten Island facility had more than 6,000 residents. It was America’s largest state-run institution for people with developmental disabilities when a young Geraldo Rivera and a TV news crew showed up unannounced in 1972.

You can see his reports here and here. WARNING: Images are definitely unsettling.

Seven years earlier, Senator Robert Kennedy also visited Willowbrook unannounced. He said he found thousands of residents “living in filth and dirt, their clothing in rags, in rooms less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo.” He said the place “borders on a snakepit.”

I raise this not simply for the history lesson, but to emphasize the truth that policy makers cannot adequately address current issues without knowing their history – whether it’s criminal justice, the environment and, in my area, treatment of people with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

Rivera’s expose, and a subsequent major lawsuit by families, compelled New York State to reform. It was driven not only by scandal, but also the understanding that people with developmental and intellectual disabilities will live more dignified and productive lives if they are integrated into communities (and liberated from impersonal, often disgusting, state institutions).

And so the state ended “warehousing” in huge facilities – like Willowbrook, Letchworth Village in Rockland County and too many others – and replaced that with a network of community-based group homes run by non-profits licensed and regulated by Albany and funded at levels set by the Governor and the Legislature.

After Willowbrook, New York State also expanded community services, increased the quality and availability of day programs and established the right of children with disabilities to a public education. The state declared that this new system would work to create more therapeutic and responsive environments, increase personalized supports and give persons with developmental and intellectual disabilities the personal and community relationships that help people thrive.

Knowing that few things create normalcy like a paycheck, New York also enacted an innovative and progressive program to create economic opportunities for people with disabilities – ie, folks who had previously been shut out of the labor force or, worse, warehoused in inhumane institutions. The Preferred Source Program was created in 1975 to, as the late Gov. Mario Cuomo might say, help people with disabilities achieve the dignity of earning their own bread. It gives non-profits that support people with disabilities a chance to provide goods and services to government agencies.

Many of the cleaners you see in government buildings are hired through this program, as well as workers who have cleaned Metro North stations during the pandemic. As you may have seen on Empire Report last week, the company that fulfilled orders for Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s NY Tough poster was retained the same way.

Yes, the Preferred Source Program is working very well. The Rockefeller Institute of Government found that the Preferred Source Program has created thousands of jobs for people with disabilities (and turned them into taxpayers), reduced government public assistance costs, and generated $368.9 million in economic output for New York in 2018 alone.

And yet in New York the jobless rate for people with disabilities is a shocking 67 percent.

We can do better. As a state, we must do better.

As we approach the end of October and the close of National Disability Employment Awareness Month, we celebrate the personal and societal value created when people with disabilities are in the workforce. As Gov. Cuomo and the Legislature wrestle with the fiscal challenges ahead, they mustn’t do so on the backs of New Yorkers with disabilities. They must continue to expand opportunities, not limit them.

Perhaps they can remember the words of President Bill Clinton: “The best social program is a good job.”

Maureen O’Brien is President/CEO of New York State Industries for the Disabled.