What Happened? And What’s Next?

Introduction

I wrote my last Substack post, which described the similarity of many public policy issues in London and New York, on January 8, 2025. I became engaged in another public policy project over the next six months, which I’ll talk about at another time. I am thankful to my colleagues, Sally Dreslin and Adrienne Anderson, for keeping the Step Two Policy Project flame alive while I’ve been away.

Obviously, a lot of things happened in the last six months, most notably the tectonic shifts in nearly every aspect of public life because of the actions of the Trump administration. Even the prospect of significant policy changes under Pres. Trump affected New York State’s annual ritual of budget-making. The FY 26 New York State Executive Budget and subsequent negotiations with the legislature occurred as if an enemy army were marshaling its forces just beyond the border, but everyone had agreed to pretend it wasn’t there.

From the standpoint of healthcare in New York State, which is the principal preoccupation of the Step Two Policy Project, the passage into law of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) on July 4, 2025, was highly consequential. What comes next for healthcare in New York is still a puzzle that policymakers and stakeholders are now beginning to confront.

The New York State FY 26 Enacted Budget

New York State’s FY 26 Budget, which was signed into law on May 9, 2025, contained less drama than almost any New York State Budget in my memory. Many observers called this an election year Budget because of its numerous spending initiatives and relative absence of controversial proposals. I thought a better name for it would be a force majeure Budget, because everyone involved fully expected that reductions in federal support for Medicaid and other areas would be sufficiently deep that the Hochul administration would be forced to declare that there had been a force majeure event that would necessitate significant changes in the current Budget. As it happened, the gamble on having one last big-spending budget before the day of reckoning from federal cuts appears to have paid off. As described below, the impact of the OBBBA will be relatively minimal prior to the next fiscal year.

Total State Operating Funds spending in the FY 26 Budget is forecasted to increase by 9.3%. As we’ve discussed before, Gov. Hochul has been less focused on limiting spending increases in her Enacted Budgets than many of her predecessors. However, actual spending growth tends to come in below the amounts forecasted in the Enacted Budgets. For example, the FY 25 Enacted Budget forecasted an increase in State Operating Funds spending of 9.7% but actual State Operating Funds spending in FY 25 rose by only 4.0%.

By the narrower definition of Medicaid spending used in the Budget – DOH-only Medicaid – spending in FY 26 is forecasted to grow by $4.2 billion or a 13.5% increase, while Medicaid spending under the broader definition of Medicaid that includes DOH and other agencies increased by 17.1%. Even without significant reductions in federal assistance resulting from the OBBBA, this rate of growth would be unsustainable. The FY 25 Executive Budget emphasized the administration’s recognition that the growth in Medicaid spending was unsustainable. The FY 26 Budget documents did not reiterate this proposition, even though the rate of growth in Medicaid spending in the FY 26 Budget is much greater than the year before, perhaps because it is now seen as too obvious to mention.

The primary culprit in the rise of Medicaid spending continues to be the inexorable growth in enrollment and spending on home and personal care – more than 90% of which is spent on personal care and a majority of which is delivered through the Consumer Directed Personal Assistance Program (CDPAP). Home and personal care are primarily financed by managed care plans through the managed long-term care (MLTC) program, although approximately 15% is financed through fee-for-service. According to the Medicaid Global Cap Report for the fourth quarter of FY 25,[1] State spending on home and personal care through the MLTCs and fee-for-service reached $11.3 billion, an increase of 13.3% from the prior year.

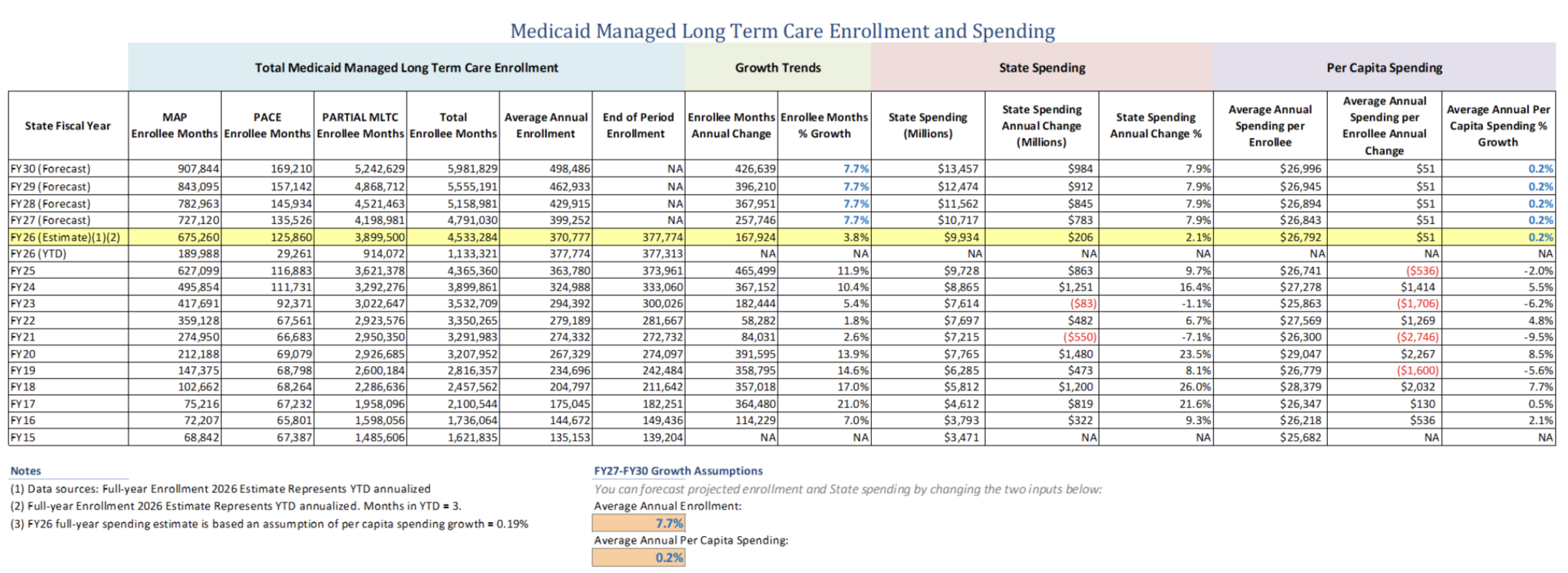

Surprisingly, in light of the fact that long-term care in general and personal care in particular are by far the largest and fastest-growing parts of the Medicaid budget, the FY 26 Budget documents do not break out historical spending or forecasts on this program, although the information is included in the quarterly Medicaid Global Cap Report, generally published with at least a four-month lag. More real-time information about MLTC enrollment can be gleaned from monthly MLTC plan enrollment published by DOH. Through the first four months of FY 26, MLTC enrollment (and presumably spending) continues to grow at a double-digit annual rate, despite efforts to bend the curve of growth.

Because having a better sense of ongoing trends can create insights about future Medicaid policy decisions, the Step Two Policy Project put together a forecasting spreadsheet that can be accessed here, and is attached as Appendix A. Three months do not make a trend, but there is some indication in the data that the rate of growth in MLTC enrollment may actually be slowing for the first time in years. The annualized rate of enrollment growth in FY 26 based on the first quarter’s data is 3.8%, considerably slower than the average annual rate of growth of 9.3% over the three prior fiscal years. If this trend holds, and based on the other assumptions in our spreadsheet, the back-of-the-envelope analysis suggests growth in MLTC enrollment in FY 26 of 6.9% and an increase in State share spending in FY 26 of $10.2 billion.

If the rate of growth is slowing, that may be partially attributable to the Hochul administration’s effort to consolidate Fiscal Intermediary (FI) services in CDPAP from roughly 700 FIs to a single FI along with a dozen or so subcontractors who will participate in an effort by the administration to mitigate intense stakeholder opposition to its plan.

Despite facing intense stakeholder blowback, it appears that the administration will ultimately succeed in the transition to a single FI. The administration is to be commended for taking on this controversial but necessary reform. Time will tell whether this initiative will reduce the growth in the program. The question is whether the greater ability to rein in FI marketing efforts that is possible with a consolidated FI structure will be enough to overcome the heretofore unstoppable demand for personal care services under the generous terms of the State’s personal care program.

The administration’s central defense of its FI consolidation is that the change would not affect benefits or eligibility for personal care services. By contrast, some of the proposals to control spending on home and personal care that were enacted in the FY 21 Budget pursuant to recommendations from the Medicaid Redesign Team II (MRT II), included not just process changes but also incremental changes in benefits and eligibility. These proposals affecting benefits or eligibility could not be implemented until recently because they were blocked by the Maintenance of Effort (MOE) provision tied to enhanced federal Medicaid funding under the Covid relief package, which prohibited any reductions in benefits or eligibility.

Now that the MOE is no longer a constraint, the Hochul administration is beginning to move forward with at least one of the more significant and controversial recommendations, which would tighten eligibility requirements for personal care services to require a minimum of three (for some special populations, the minimum will be two) activities of daily living (ADLs) for new enrollees who are eligible for long-term services and supports. Even though existing recipients of these services are grandfathered, this will be a very controversial policy. Nevertheless, the new requirement is projected to reduce the rate of growth in use of the services by approximately $300 million annually, an amount that should grow over time given the typical churn in the program, which may be accelerated by increased churn resulting from the six-month eligibility checks in the OBBBA.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The OBBBA was signed into law by Pres. Trump on July 4, 2025. Despite some complaints by hardliners in the House that the Senate bill fundamentally changed the bill adopted by the House, the House adopted the Senate bill without changes in order to meet the July 4, 2025 deadline set by Pres. Trump. The Senate bill reflected the elimination of some spending cuts because of rulings by the Senate parliamentarian enforcing compliance with budget reconciliation rules. This included the removal of a penalty for covering non-citizens, which would have cost New York almost $1 billion. But the Senate bill also added a number of additional Medicaid cuts that will increase the reductions facing New York State, albeit to be phased in over a long period of time.

There are many good summaries of the national ramifications of the Medicaid reductions in the OBBBA, which the Congressional Budget Office projected will result in federal savings of approximately $1.02 trillion over the next 10 years.[2] In addition, Jillian Kirby and the Rockefeller Institute of Government have produced an excellent analysis of the OBBBA and its specific impact on New York State, in An Analysis of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA’s) Impact on Healthcare for New York, published on July 10, 2025.

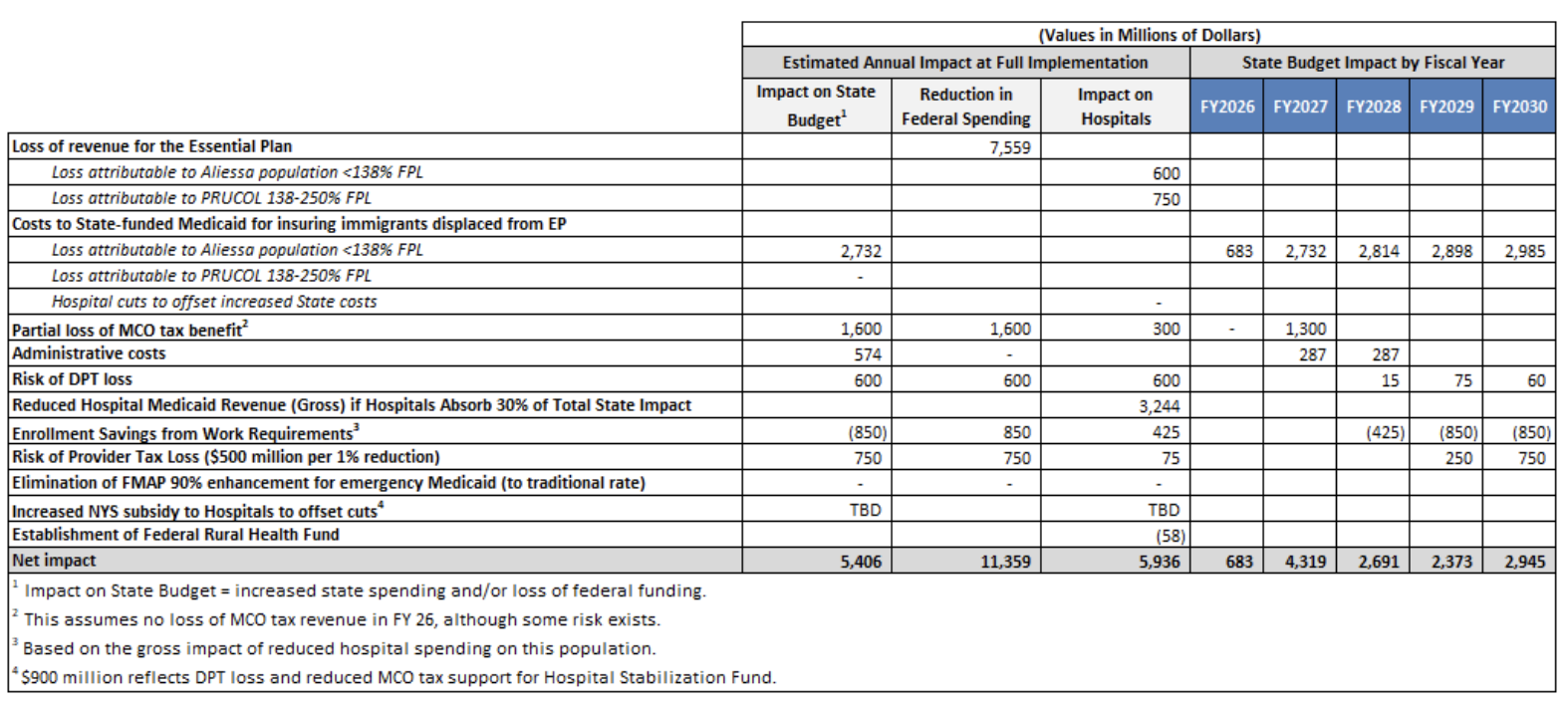

Even with this close analysis, there remains some ambiguity about how certain provisions of the OBBBA and related regulatory actions will affect New York. The Department of Health (DOH) has not yet released an official accounting of its interpretation of the negative impacts of the OBBBA. The table below reflects my understanding of the impact of the OBBBA and pending regulatory actions based on information that was circulated by the Governor’s office, DOH, or the hospital trade associations during the development of the final OBBBA, as well as reference to Jillian Kirby’s analysis.

The two biggest impacts of the OBBBA on both the New York State budget and the hospital sector – the exclusion of coverage for non-citizens by the Essential Plan and the loss of revenue from the Managed Care Organization (MCO) Tax adopted in the FY 25 Budget – will go into effect by January 1, 2026, which includes the fourth quarter of New York’s FY 26 fiscal year. For a variety of reasons, including the timing of payments, the effect of the OBBBA FY 26 will likely be small in FY 26, but the total impact in FY 27 appears to be approximately $4.3 billion.

Ironically, the only source of potential Medicaid savings to the State, which would result from a reduction in Medicaid enrollment due to new work requirements, will not take effect before 2028. Moreover, such savings may prove less than the consensus estimates (which are reflected in the table above) if New York is able to implement work requirements and/or six-month eligibility checks in a way that results in fewer enrollees being kicked out of the program.

Depending on various assumptions (including how much of the negative impact on the State budget results in State savings actions that reduce Medicaid payments to hospitals), the impact on hospitals in New York could be in the neighborhood of $6 billion or more annually, with impacts of approximately $2 billion or more beginning in FY 27.

In terms of impact on individuals, at least 224,000 individuals now covered by the Essential Plan will lose coverage beginning on January 1, 2026. Many more are expected to lose coverage when enhanced ACA premium subsidies put into effect during the Biden administration sunset in October 2025, which will raise the cost of insurance for many individuals purchasing Qualified Health Plans. The work requirements of the OBBBA to be implemented in 2028 will further increase the number of New Yorkers without health insurance coverage. This reduction in the number of insured New Yorkers will significantly increase the amount of uncompensated care for hospitals and other providers.

By far the largest impact of the OBBBA on New York is the loss of federal funding (technically called “federal financial participation”) for most non-US citizens, so it is worth discussing this in some detail. The new restrictions under the OBBBA will result in the loss of approximately $7.6 billion of federal revenue to the Essential Plan in New York as a result of approximately 730,000 New Yorkers losing their coverage under the Essential Plan.

Even though Medicaid is expected to cover close to two-thirds of these individuals, the loss of $7.6 billion of revenue paid out through the Essential Plan will have profound effects on hospitals, community health centers, and other providers of care services, because Essential Plan reimbursement rates are approximately double that of Medicaid reimbursement rates.

The 730,000 New Yorkers who will lose coverage under the Essential Plan effectively fall into two categories under the broader heading of non-US citizens who are lawfully present in the United States but who are barred from federal support under Medicaid by two related restrictions, known by their acronyms PRUCOL and PRWOA. PRUCOL stands for Permanently Residing Under Color of Law.

Approximately 506,000 of these individuals are part of the “Aliessa” population, named after the New York Court of Appeals case Aliessa v. Novello (2001), which held that the New York State Constitution requires the State to provide State-only healthcare coverage to residents of New York who are lawfully present in New York but who are ineligible for federal financial participation under Medicaid solely by virtue of their immigration status. The other approximately 224,000 affected individuals, who are lawfully present in New York but have incomes too high to be eligible for Medicaid, are simply referred to as the “PRUCOL” population, even though some of them are in a similar category as PRWOA, the acronym for individuals covered by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act.

Following the Aliessa decision, New York State began to provide State-only funded Medicaid to individuals who would be eligible for Medicaid but for their immigration status, i.e., typically individuals with incomes up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). With the passage of the ACA and the creation of the Essential Plan in 2015, the transfer of the Aliessa population to the Essential Plan provided about $1 billion in budget relief to the Medicaid program. The PRUCOL population with incomes above 138% of FPL would not be eligible for Medicaid solely because of their immigration status. However, if their incomes are below the maximum under the Essential Plan (now 250% of FPL), they have been eligible for coverage through the Essential Plan. The Essential Plan has always had sufficient surplus federal funding so that it could cover the costs of the PRUCOL population [though it did not receive additional federal funding for this population].

The State has estimated that restoring State-only Medicaid coverage to the Aliessa population will require approximately $2.7 billion in additional State spending. The State has not estimated the cost of providing State-only coverage to the 224,000 individuals described as the PRUCOL population, which suggests that the administration is not currently planning to provide healthcare benefits to this group. Few individuals in this income bracket can afford the cost of commercial insurance without premium subsidies, so we can expect that nearly all of these 224,000 individuals will become uninsured.

The State budget is also expected to lose $1.6 billion of federal funds derived from the MCO tax adopted in the FY 25 Budget, but not until roughly June 2026 – and so will also affect the FY 27 budget. Jillian Kirby points out in her analysis that there is a risk of the loss of revenue from the MCO tax in FY 26 because of pending regulations submitted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on May 15 2025, which state that “If this rule is finalized, States that received the most recent waiver approval for their tax that does not comply with § 68 (e)(3) 2 years or less from the effective date of the final rule would not be eligible for a transition period.” Although this regulation would appear to apply to New York, State officials seem to be operating on the assumption that it would not lose funding in FY 26, but only in FY 27.

Most of the other OBBBA reductions in federal funding under Medicaid will not take effect for 1-2 years or even longer. For example, it appears that the loss of approximately $600 million related to State Directed Payments, in New York, known as the Directed Payment Template (DPT) program, will only begin to phase out DPT payments above Medicare rates (which are worth approximately $600 million a year to New York) beginning in FY 28, but this assumes that New York’s DPT plan for FY 26 was submitted or approved by July 4, 2025.

Reductions in federal support associated with provider taxes[3], which may ultimately cost New York[4] approximately $1.5 billion, will not begin a six-year phase-in until 2028. Similarly, work requirements, which perversely may provide budget relief in New York by reducing the Medicaid rolls, do not go into effect until December 31, 2026.

Finally, New York has estimated its administrative costs in connection with work requirements and changes to Medicaid eligibility assessments will cost $574 million, although much of this may be capitalized and thus eligible for bonding – spreading the cost over many years.

The State budget is also at risk to the extent that the State concludes it must provide additional support to hospitals or other providers to mitigate the impact of the OBBBA provisions on them. The term “hospitals” as we are using it here really refers to hospital-based healthcare systems, which often realize 30%-50% of their revenue from outpatient services.

New York’s hospital associations have estimated that these provisions will cost hospitals in the neighborhood of $6 billion directly and up to $8 billion when including so-called “ripple” events once fully implemented, as reflected in the table earlier. This loss represents roughly 7% of New York’s total hospital revenue of approximately $120 billion, a staggering decline in operating margin given that nearly 60% of hospitals in New York State already operate at flat or negative operating margins (including depreciation expenses). Without the State providing operating subsidies to make up for at least some of this lost revenue, New York’s hospital infrastructure may look very different when the dust settles.

What’s Next?

It has been in the interest of both proponents and opponents of the OBBBA to make the reductions in federal Medicaid funding appear as extreme as possible. The Republican proponents of the OBBBA are trying to demonstrate their fiscal responsibility bona fides, as well as enacting spending reductions to comply with Budget reconciliation rules that require increased budget deficits to be offset by spending reductions. The opponents of the OBBBA are trying to make the budget cuts appear as dire as possible to forestall the bill’s enactment. Now that it has become law, the opponents have a similar motivation to assume the worst in order to soften the ground for hard decisions in the upcoming State budget.

That said, the loss of more than $4 billion in federal funding in FY 27 will be much more difficult to manage than the currently projected FY 27 overall budget deficit of $5.5 billion (excluding a $2 billion “transaction reserve”). Not all deficits are created equal. For example, the $5.5 billion deficit is based on a conservative assumption of tax revenue growth of 2.6% compared to the average 4.4% annual growth experienced over the last two decades and 6.0% revenue growth projected for FY 26. Each percentage point of the tax revenue growth is worth approximately $1.2 million. In short, absent the OBBBA impacts, the FY 27 budget is in pretty good shape.

However, the approximately $4.3 billion hole that the OBBBA has blown in the FY 27 Medicaid budget cannot be absorbed without significant expense reductions, tax revenue increases, or some combination of the two.

New York State’s Budget Director, Blake Washington, spoke to this last week, saying, “These are going to require some really challenging discussions in the next handful of months. … But there’s no taxing our way out of this; there’s no way the state of New York can finance what’s been foisted upon us.”[5]

There seems to be little interest among legislative leaders to return for a Special Session later this fall to begin to address the FY 26 loss of roughly $700 million in federal support. All parties are likely to prefer getting through FY 26 using reserves or other revenue re-estimates and expense “avails” to get through FY 26 rather than dealing with this seismic change to the State budget on a piecemeal basis.

The real action will begin with the FY 27 Executive Budget, which will be introduced in January 2026. In addition to Medicaid, there likely will be additional negative impacts on the State budget beginning in FY 27, including reductions in non-military discretionary programs as outlined in Pres. Trump’s “top lines” discretionary budget, released in May 2025.[6] Moreover, the prospect of other federal budget actions, such as changes to the State share of SNAP funding in the OBBBA that won’t take effect right away, will further complicate resolving the State budget.

The State has three basic options for managing the fiscal impact of the OBBBA: seeking to get out of its obligation to cover the Aliessa population with State-only Medicaid funding by reopening the case; increasing taxes to offset the impact of the loss of federal support; and reducing spending in Medicaid to make up for lost federal funding.

Reopening the Aliessa Case

The most significant fiscal impact of the OBBBA is the prohibition of using federal funds to cover nearly all non-citizens, combined with the conclusion under the Aliessa v. Novello Court of Appeals decision in 2001 that the State Constitution and the federal 14th amendment Equal Protection Clause require the State to provide Medicaid coverage to non-citizens who are lawfully present in New York and who would be eligible for Medicaid but for their immigration status, even if federal financial participation for that group was not available.

The Court of Appeals decision in Aliessa stated: “This Court, however, has interpreted article XVII, § 1 [of the New York State Constitution] as prohibiting the Legislature from ‘refusing to aid those whom it has classified as needy’.” In simple terms, since the legislature had determined that citizens with incomes at or below 138% of the federal poverty level were “classified as needy,” the State could not refuse to aid non-citizen lawful residents of the state meeting the same classification of need just because the federal government would not provide support for those individuals.

The argument for reopening the Aliessa case would be that the OBBBA creates new grounds for a federal preemption argument. I have not practiced law in 40 years, and real lawyers might reach a different conclusion from my own, but my reading of the Aliessa decision is that although it relies on both the State Constitution and the 14th amendment, the Court of Appeals essentially held that it would impose that requirement on the State on the basis of the State Constitution alone. The argument of federal preemption was dismissed with the statement that “the Federal government may not authorize the State to violate the State Constitution.” Other lawyers may reach a different interpretation – and if Rep. Elise Stefanik were Governor, you could almost count on this option being tested in court – but I think the conventional wisdom will be that the OBBBA does not discharge the State’s obligation to provide the Aliessa population with Medicaid using State-only funding.

Beyond the legal interpretation, I’m hard-pressed to believe that veto-proof Democratic majorities in both the NYS Assembly and Senate would agree to drop Medicaid coverage for non-citizens who would be Medicaid eligible but for their immigration status, even though the legislature and the executive may be willing to allow care coverage to lapse for the 224,000 non-citizens (i.e., PRUCOL) who will be denied continued eligibility for healthcare coverage under the Essential Plan.

Tax Increases

Notwithstanding Blake Washington’s comments that the State cannot tax its way out of this problem, there is little doubt that a significant segment of the State Senate and Assembly, as well as affected stakeholders, will push for increased revenue to mitigate, if not eliminate, spending reductions due to the loss of federal funding under the OBBBA.

Assuming there are proposed revenue increases, what shape can they be expected to take? Ironically, the tax increase proposals of Assemblyman Mamdani, the proceeds of which he proposes to use to support his spending initiatives in New York City, may prove to be a reference point for discussion about State tax increases to mitigate the impacts of the OBBBA cuts. Assemblyman Mamdani proposed raising $4 billion by increasing New York City income taxes by 2% for taxpayers with incomes of $1 million or more, without specifying whether the $1 million threshold applies to joint filers as well as individual filers. By contrast, the high-earner surtax in New York State that was adopted in 2020 and extended in the FY 26 Budget to 2032 increased State income taxes by 2% for individual filers with incomes of $1.1 million and joint filers with incomes of $2.2 million and by 3.35% for taxpayers with incomes of $25 million or more.

A conservative estimate is that each 1% in an additional increase in the State income tax would raise approximately $2.5 billion. The scoring is based on the statement in the FY 26 Executive Budget Briefing Book to the effect that the extension of the top rates would generate “over $5 billion annually on a tax year basis”[7] and the New York State Senate Finance Committee’s Economic and Revenue Report, which said that the high-income surcharge “will add approximately $7.2 billion in new receipts in SFY 2025-26.”[8]

Assemblyman Mamdani has also proposed increases in New York State’s corporate income tax rate from 7.25% to 11.5%, which would generate approximately $5 billion annually, arguing that it would just equalize New York State’s corporate income tax rate with that of New Jersey. Assemblyman Mamdani has always neglected to point out that, though, this would result in corporate income taxes or equivalent charges related to the MTA[9] of approximately 23.5% for corporations based in New York City, which generate roughly 85% of the total amount of corporate income taxes in New York State – a level higher than the federal corporate income tax rate of 21%.

Gov. Hochul has expressed firm opposition to personal income tax increases in New York City or New York State. Many news accounts report that as opposition to all tax increases, although the statements I’ve read do not as clearly oppose an increase in the corporate income tax rate.

It is true, as Assemblyman Mamdani points out, that corporate income taxes in New York are based on the apportionment of the corporate taxpayer’s taxable income in the United States on the basis of sales in New York State, as opposed to the corporation’s payroll or assets located in New York State. Although exceedingly high corporate income tax rates might well result in corporations charging higher prices in New York City to offset these taxes, the sales apportionment basis of corporate taxation probably reduces the likelihood that increased corporate income tax would lead companies to exit the State compared to the risk that ever-increasing personal income taxes would increase the outmigration of wealthy taxpayers.

Medicaid Spending Reductions

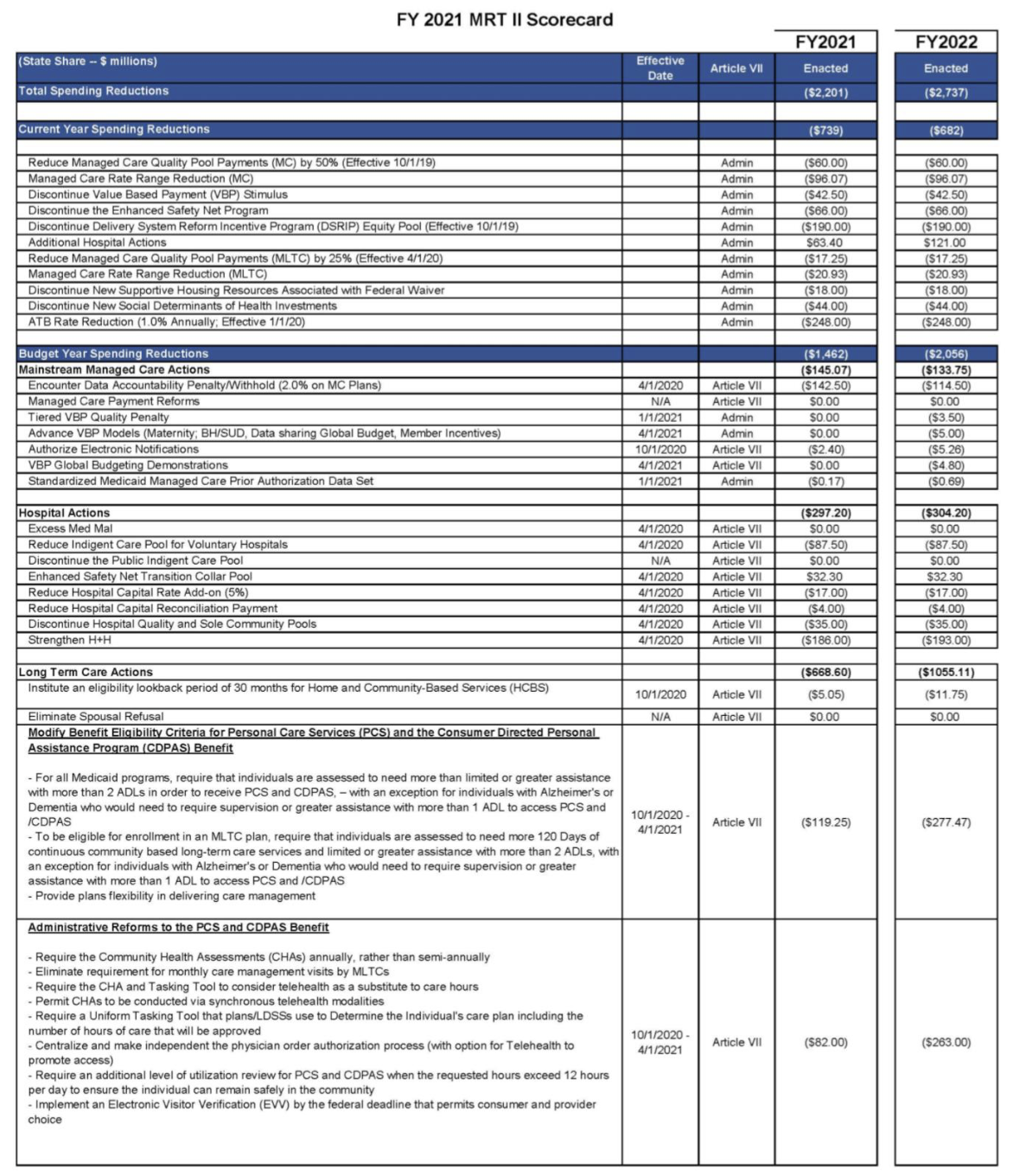

The starting point for understanding the State’s options to reduce Medicaid spending is an appreciation of the last comprehensive effort to bend the curve of growth in Medicaid expense, which was the MRT II. In 2019, the unexpected surge in long-term care costs – mostly attributable to CDPAP – forced the State to “roll” $1.7 billion of payments into the following fiscal year. Throughout 2019, culminating in the formation of the MRT II, in my role as Deputy Sec. for Health and Human Services, I led a working group that included DOH’s Office of Health Insurance Programs (OHIP) and the Health Unit of the Division of Budget.

This working group sought to identify spending reductions that would be large enough to bend the curve of Medicaid spending without significantly changing benefits or eligibility or imposing pressures on providers that they would be unable to absorb. When the MRT II was constituted, it began with that outline of ideas and then spent three months on stakeholder engagement in public hearings in an effort to develop a comprehensive set of proposals to be considered in the FY 21 Budget negotiations.

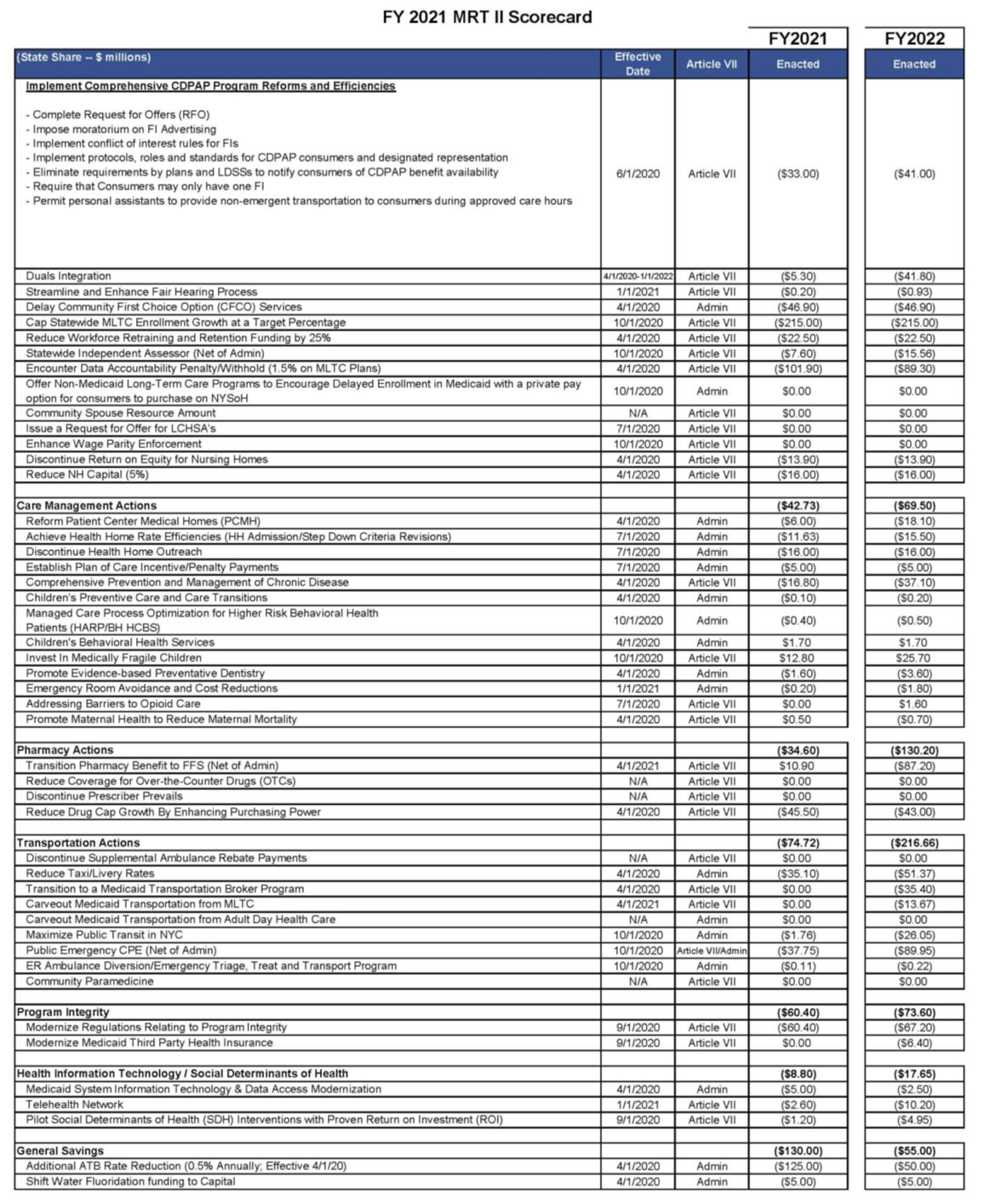

Appendix B includes the FY 21 MRT II Scorecard, showing both the executive proposals totaling $2.7 billion and the proposals that made it into the FY 21 Enacted Budget, which totaled $2.2 billion, including nearly $1.1 billion in State spending related to long-term care. Most of the other substantial actions were the kind of relatively small-bore savings actions that are typical in the Medicaid budget-making process.

As it happened, the Covid pandemic made most of the more consequential MRT II recommendations moot, at least for several years. The federal government provided an extraordinary amount of financial assistance to hospitals and other providers. Acceptance of that assistance required the State to comply with the Maintenance of Effort provision, which blocked many of the proposed savings actions in the MRT II recommendations. Without trying to track the history of each proposal, the extent of MRT II accomplishments is perhaps best measured by the fact that State Medicaid spending in FY 21 was a total of $22.3 billion[10] while total State Medicaid spending in FY 26 is forecasted to be $35.4 billion.[11]

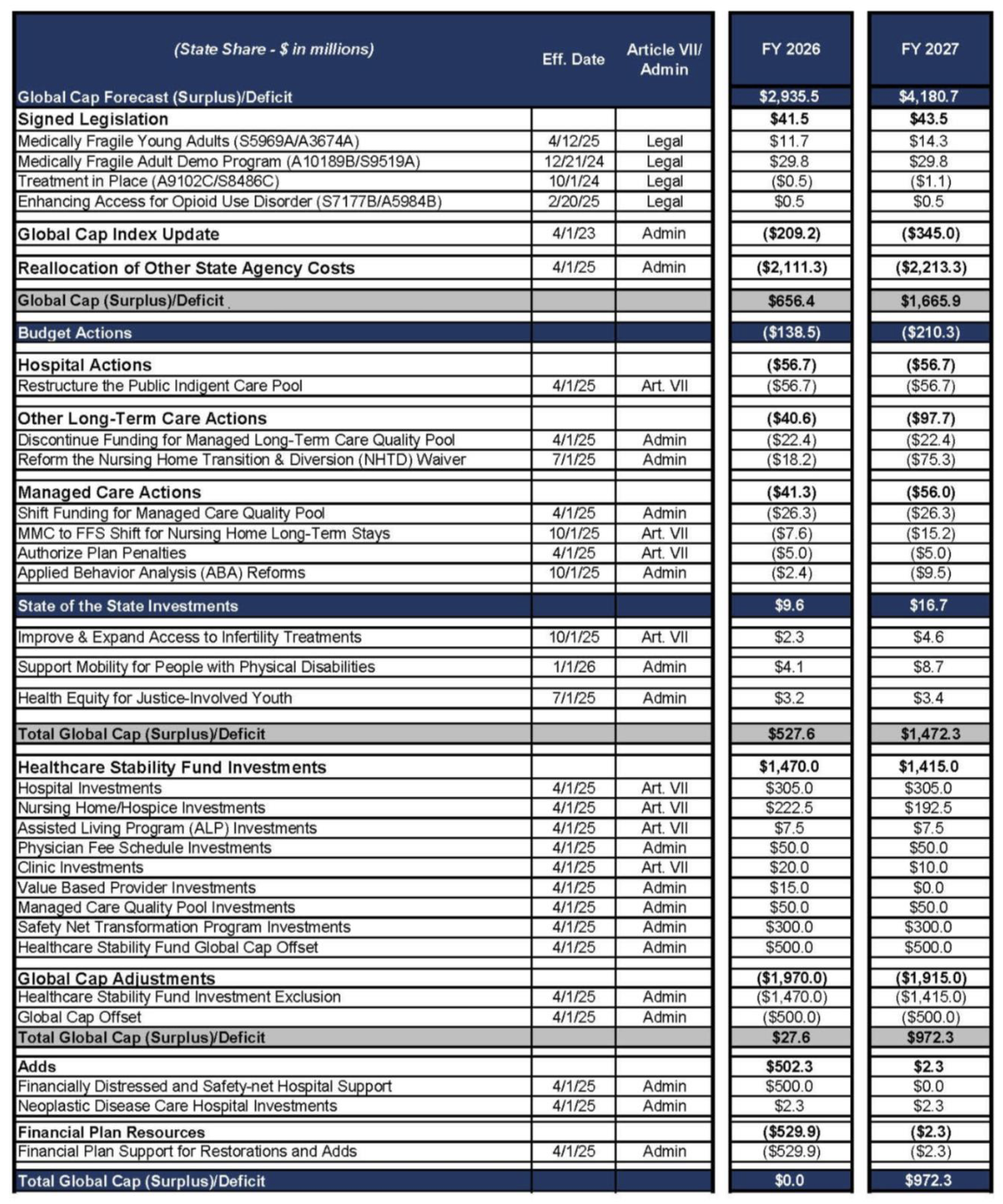

Appendix C includes the Medicaid Global Cap scorecard for the FY 26 Enacted Budget. The Global Cap was balanced in FY 26 and FY 27 by using an exceptional amount of financial engineering – the movement of approximately $2.1 billion in Medicaid spending from the Global Cap to the budget of other state agencies that rely on Medicaid, exclusion from Global Cap of approximately $1.5 billion in spending for the Healthcare Stability Fund based on revenue from the MCO tax, and an additional $1 billion from a Global Cap offset and additional General Fund financial plan support for restorations and adds. To some extent, you can view the Healthcare Stability Fund and other investments in the FY 26 budget as the most vulnerable programs for spending reductions, but these investments were made in response to deep needs in the hospital and nursing home sectors, in particular.

I hope that the Hochul administration creates a structured and transparent process for developing a plan to select and implement a combination of the options for addressing the loss of federal revenue for Medicaid. A stakeholder-engaged process such as MRT II had certain drawbacks, but on balance, it helped illuminate what the options were and helped build consensus for difficult decisions, such as the significant changes proposed for the personal care program.

A crisis is a terrible thing to waste – as the cliché goes. It’s too soon to say whether the loss of $4.3 billion in federal Medicaid funding for the State and the prospect of even larger financial impacts on the hospital sector will amount to a true crisis – to some extent it depends on whether the State will have sufficient means from new or existing sources to cover a large portion of the shortfall. But at a minimum, fundamental questions about New York’s ability to maintain its particularly generous Medicaid program and what happens when financial unsustainability runs headlong into the political inability to reform programs.

Conclusion

Given that FY 26 budget-making included so few controversial Medicaid proposals, one that stood out was the effort to block DOH’s effort to carve School-Based Health Centers into managed care beginning April 1, 2025. This action had been blocked by the legislature for many years, but the administration seemed intent on moving forward this year after the DOH issued a letter in September 2024 mandating the transition occur by April 1, 2025, and Gov. Hochul vetoed a bill that would have permanently prevented the move. In the end, the Enacted Budget included a prohibition of the carve-in before April 1, 2026.

In Albany, when a controversial decision is pushed out to a date past the point at which another vote would create the opportunity to further kick the can down the road, the conventional wisdom is that it is more likely than not that opponents will be able to block the measure before it can be implemented. The OBBBA similarly defers the effective date for many of its most controversial actions until after the midterm elections in 2026. Time will tell whether the delayed effective date of many of the most significant Medicaid provisions in the OBBBA means that the provisions will be eliminated before their effective date or watered down in their implementation.

I share the view of Reihan Salam, President of the Manhattan Institute, that many of the Medicaid spending reductions – a majority of which come from work requirements that don’t go into effect until 2028 – are largely performative. As Mr. Salam wrote recently:

“The cuts aren’t real. To lower the staggering sticker price of the reconciliation bill, Republican lawmakers had to identify hundreds of billions of dollars of CBO-approved budget cuts. But they also had to convince hospitals in their home districts that those budget cuts wouldn’t actually materialize. They did this by coming up with a series of pseudo reforms that state governments could easily game.” (“Is the One Big Beautiful Bill a Masterstroke – Or a Disaster,” The Free Press, July 6, 2025.)

Unfortunately, New York is almost unique among states in the extent to which the OBBBA will significantly reduce federal funding to the State almost immediately, before another vote which could give Congress the chance to postpone the day of reckoning. Moreover, the nature of these cuts will be difficult if not impossible for the State to “game” in implementation.

The lesson of MRT II is that an effort to close a $4.3 billion budget gap with Medicaid spending reductions alone would require some combination of meaningful changes in Medicaid benefits or eligibility, much greater willingness to allow hospitals and nursing homes to close for want of State operating subsidies, or fundamental program changes such as elimination of partial capitation MLTC plans. I don’t believe the political system is capable of this level of change, which is why I believe increased tax revenue or substantial use of reserves will likely be part of the solution.

In any event, if the FY 26 Executive Budget in negotiations was a real snoozer, the FY 27 budget season promises to be the most consequential in many years. It will almost certainly bring to a head the clash between, on the one hand, the progressive instinct to continue to raise taxes to support New York’s wide and deep safety net, and, on the other hand, the moderate impulse to constrain new taxes and focus on spending reductions. If they sold season tickets for the Budget process, now would be a good time to buy.

Appendix A: Step Two Policy Project’s Medicaid Managed Long Term Care Enrollment and Spending Table

Available for download as an Excel workbook here.

Appendix B: Final MRT II Scorecard

Appendix B (continued)

Appendix C: 2026 Enacted Budget Medicaid Scorecard

[1] See p. 14.

[2] Health Provisions in the 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation Bill. KFF. Updated July 8, 2025.

[3] Congressional Research Service. Medicaid Provider Taxes. Updated December 30, 2024.

[5] Budget director says NY health care will be ‘destabilized’ by federal cuts. Justin Raga. Times Union. July 10, 2025.

[6] Executive Office of the President: Office of Management and Budget. Fiscal Year 2026 Discretionary Budget Request. May 2, 2025.

[7] New York State Office of the Budget. FY 2026 Executive Budget Briefing Book. See p.37.

[8] New York State Senate Majority Conference Finance Committee. 2025 Economic and Revenue Report. See p. 33.

[9] Certain employers and self-employed individuals operating within the “Metropolitan Commuter Transportation District” are subject to a payroll tax, referred to as the MTA surcharge.

[10] New York State Office of the Budget. FY 2022 Enacted Budget Briefing Book. See p.106.

[11] New York State Office of the Budget. FY 2026 Enacted Budget Briefing Book. See p.18.