Rural Healthcare in New York

The squeaky wheel gets the oil, as the saying goes, so it is not surprising that the challenges of rural healthcare do not command as much attention in Albany as the healthcare challenges of New York’s urban areas. The nature of the challenges and potential solutions to providing healthcare services for rural New Yorkers is in many respects different from that of serving urban and suburban New Yorkers. To be successful, New York’s health policies need to support the unique needs of rural communities.

Sally Dreslin, the Executive Director of the Step Two Policy Project, has posted an 18,000-word Policy Brief, Healthcare in Rural New York: Current Challenges and Solutions for Improving Outcomes, which offers valuable insights about the challenges the rural healthcare system is experiencing and offers a range of policy recommendations to help meet those challenges. The Policy Brief is accompanied by the extensive amount of data analysis contained in Disparities in Rural and Urban Mortality: New York State Chartbook, which was lead-authored by Adrienne Anderson. The Chartbook’s findings demonstrate the extent to which health outcomes in rural areas are worse than in more urbanized parts of New York State. In most cases, these disparities have become much more pronounced over the last 20 years.

A discussion of the challenges of rural healthcare seems particularly appropriate during this election season, which continues to reveal the stark divide between rural America and its urban and suburban counterparts. Given the important place that rural life holds in the American imagination, it may be no accident that the Vice-Presidential candidates of both political parties highlight their upbringing in small towns, albeit one with an idealized boyhood and another who faced more of the modern challenges of rural life. In any event, rural America feels left behind. Rural New York is no exception to the broader trend, which is reflected in the demographic trends of a smaller and older population with deep socioeconomic challenges.

There is no universal definition of what constitutes “rural.” Sally’s Policy Brief and the Chartbook use definitions from the 2013 Urban Rural Classification Scheme for Counties, which includes 24 counties in New York that have an average population density of approximately 55 people per square mile. These 24 rural counties in New York only experienced a total population decline between 1970 and 2020 of about 12%, but the average age of the population rose from 28.3 years in 1970 to 45.8 years in 2020.

Two of the most important metrics that serve as indicators of a population’s health are overall “premature mortality” and “natural-cause mortality,” which excludes deaths from external causes, like accidents or suicide. The average age-adjusted premature mortality rate (i.e., including external causes) in New York’s rural counties in 2019 was 12% higher than in urban New York counties. However, as cited by a March 2024 national report from the USDA Economic Research Service, in 2019, the age-adjusted natural-cause mortality (NCM) rate[1] for the “prime working-age population,” those ages 25-54 years old, was a stunning 43% higher in rural areas than in urban areas. This represents an enormous increase since 1999, when the NCM rate for those ages 25-54 years was just six percent higher in rural areas than in urban areas. One of the important contributions of Sally’s paper is that it provides transparency about the condition of healthcare in rural New York, which should be a call to action for policymakers.

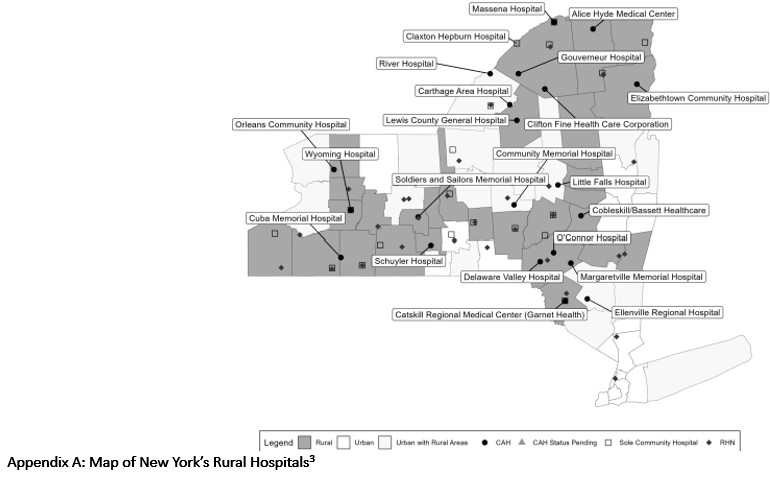

These 24 counties, which have an aggregate population of approximately 1.3 million people, host 18 Critical Access Hospitals and 21 Sole Community Hospitals. Although the term “hospitals” connotes inpatient acute care, hospitals throughout New York today encompass a significant amount of outpatient services. Rural hospitals generally derive a majority of their revenue from outpatient services, so in many respects, these rural “hospitals” really constitute the healthcare delivery system in a rural area.

Sally’s paper uses the structure of the recommendations of the American Hospital Association’s “Future of Rural Health Care Task Force” to describe initiatives undertaken by a number of rural hospitals and healthcare systems in New York. These initiatives involve public-private funding partnerships, strategic alliances, and innovations in the delivery of dental care, among others. Perhaps because necessity is the mother of invention, these institutions have been less resistant to change than some of their urban counterparts.

This gradual transformation of a number of rural hospitals and healthcare systems could be accelerated by State policy changes and certain targeted federal reforms. The strategies these policy changes should support include the following:

Reimbursement Reforms

Designation as a Critical Access Hospital (CAH) often becomes a lifeline for a rural hospital, because CAHs receive Medicare reimbursement based on 101% of their allowable costs rather than a fixed payment under Medicare’s Prospective Payment System (PPS) reimbursement methodology. While the exact difference between CAH payments and PPS payments varies based on hospital-specific factors, some analyses indicate that CAH payments under the cost-based reimbursement methodology may be 20% higher – or more – than PPS rates. Because of the age demographic of rural hospitals’ catchment areas, Medicare often accounts for 50% of all reimbursement, so the higher CAH rates may transform the financial outlook of the hospital.

As described in Sally’s paper, the CAH statute and regulations impose certain limits on CAHs. However, national experts who work with CAHs believe there is more flexibility to these requirements than is generally appreciated. The State should explore whether any of New York’s Sole Community Hospitals that are financially distressed could convert to a CAH in order to secure their financial sustainability.

Sally’s paper includes other recommendations related to reimbursement which, at a minimum, describe ways to target additional State funding, should it be available. The CAH strategy, on the other hand, purely involves ensuring financial sustainability by taking advantage of additional federal funding. As part of a broader rural health strategy, the State should provide the technical assistance necessary to fully explore additional opportunities for CAH conversions in New York.

Strategic Alliances Enabled by Regulatory Flexibility

Sally’s paper describes a number of strategic alliances among upstate hospitals. A particularly creative strategic alliance that also takes advantage of the CAH program involves Carthage Area Hospital, a 25-bed critical access hospital, and Claxton-Hepburn Medical Center, a 127-bed sole community hospital and regional referral center that includes a 40-bed inpatient psychiatric unit. In a complicated transaction that is pending final approval from the State, Carthage will also assume operations of all of Claxton-Hepburn’s acute care, emergency, and outpatient services (including its five rural health clinics). The newly established Carthage-operated CAH will be co-located with the newly established Claxton-Hepburn inpatient psychiatric hospital and a planned CPEP supported by grant funding from the NYS Office of Mental Health. The transaction was structured to meet the requirements established in the CMS Guidance for Hospital Co-location with Other Hospitals or Healthcare Facilities.[2]

Another important regulatory restraint that needs to be modernized is the DOH regulation section §600.9, which hinders the integration of services delivered by multiple providers. The regulation should be modernized to permit revenue sharing between qualified providers, even when a collaborator is not an established operator of the facility. One of the features of modern healthcare delivery is the “unbundling” of service provision to permit greater efficiency through specialization. Prohibitions of revenue-sharing need to be adapted to reflect modern business models.

Permit Rural Hospitals to Participate in Global Budgeting and Encourage Operational Rationalization

As Sally writes in her paper:

“The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, which started its Performance Year Zero in January 2017 and anticipates ending the performance period in December 2024, was implemented to test whether the predictability of having a global budget will enable rural hospitals to invest in quality and preventive care, and align the services they deliver to better meet the needs of their communities.”

Despite promising early results from the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, New York’s new 1115 Waiver limits federal support for global budget pilots to downstate hospitals. The State should explore whether CMS is amenable to permitting such pilots to be developed in rural hospitals upstate.

Rural hospitals lack the management capacity to identify and implement operational efficiencies. The State could assist this process by providing support for outside experts who could offer technical assistance to rural hospitals that are willing to pursue a Managed Service Organization model, which could provide support services more efficiently and with greater sophistication.

Workforce

Workforce shortages, which exist throughout the healthcare system, are particularly acute in rural areas. New York can help address this challenge of rural hospitals through a number of policy reforms.

New York can make licensure processes more efficient by joining the Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) and the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC). This would allow nurses to have one multistate license that enables them to practice in all member states (currently 42 states) and would provide an expedited pathway for physicians licensed in a member state to obtain a full and unrestricted license to practice medicine in other member states. Many of New York’s rural counties are close to the State’s borders.

In addition to licensure, the service-obligated loan repayment programs for healthcare professionals who agree to practice in health professional shortage areas, many of which are in rural New York, are important opportunities to recruit clinicians. These efforts would be more impactful, however, through a program (which could be housed at the State’s Empire State Development office) to support the spouses/partners of healthcare professionals who agree to practice in New York’s rural, health professional shortage areas, with employment opportunities.

In addition, New York can adopt changes to scope of practice (and permitted activities) for pharmacists, physician assistants, certified registered nurse anesthetists, dental hygienists, emergency medical technicians and paramedics, and recognize dental therapists and medical assistants, to maximize available workforce resources and promote team-based care, particularly in rural New York. Strong legislative opposition has hindered the adoption of commonsense scope of practice changes of the type that worked effectively during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Finally, along with Graduate Medical Education (GME) incentives to establish rural residency programs, New York should establish a Graduate Nursing Education (GNE) pilot for advanced practice nurses, e.g., nurse practitioners and nurse midwives, to train in rural settings, where recruiting physicians is particularly difficult.

***

When Sally and I formed The Step Two Project, one of our objectives was to focus in-depth on policy areas that are often overlooked by the crush of more urgent issues. Sally’s Policy Brief and the Chartbook on rural health do just that. Taken together, this review of both the challenges of rural healthcare and innovative responses of many rural providers, combined with its policy recommendations, can help to create a roadmap for a rural health policy agenda. This agenda could be implemented with a relatively small financial commitment but a high degree of focus and become a legacy achievement for the Department of Health and the administration.

Paul Francis is the Chairman of the Step Two Policy Project. He served as the Director of the Budget in 2007 and as the Deputy Secretary for Health and Human Services from 2015-2020, among other positions in New York State government, before retiring in May 2023.

[1] In “The Nature of the Rural-Urban Mortality Gap,” USDA Economic Research Service, March 2024, “natural-cause mortality” is defined as “all causes of death except for those attributed to external causes of morbidity and mortality, such as causes from accidents, violence, legal actions, or surgical complications.” See p. 6. Such causes are distinguished by the associated International Classification of Disease, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes. Examples of natural-cause mortality include chronic diseases, acute illness, and pregnancy-related deaths, while examples of external-cause mortality include car crashes, assaults, suicide, and overdose.

[2] Guidance for Hospital Co-location with Other Hospitals or Healthcare Facilities (Revised), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.