No New Yorker Should Have to Suffer Like Cathy Did

Is there anything worse than watching someone you love suffer until they die in agony?

Not for me.

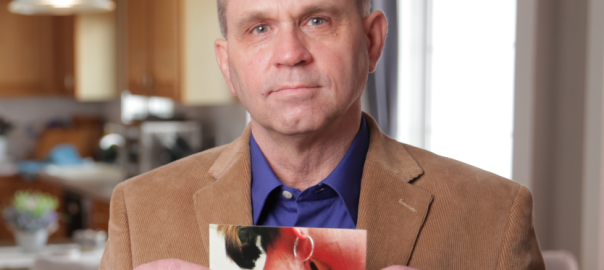

I will never get over the horrible death my late girlfriend, Cathy Quinn, endured. Cathy died, at the age of 44, June 25, 2014 after two years of suffering with tongue cancer.

Cathy didn’t want to die. She was a vibrant person who had plans for just about everything. Whether it was where we should retire in our old age, a luxury cruise, or my next delicious meal, she loved to get deep into the details. She epitomized the concept that it’s the journey, and not the destination.

A problem solver by nature, once diagnosed with cancer, Cathy was fully involved in her treatment, challenging doctors and asking probing questions. She made critical, well-informed decisions about her health care. She endured multiple surgeries, excruciating rounds of radiation and chemotherapy, and countless doctor visits and procedures.

In spite of her fierce resilience and the best efforts of doctors, the cancer returned for a fourth time in the spring of 2014 and spread throughout her body. Her doctors confirmed what she already knew. She was going to die, and she was going to die soon.

The reality of her imminent death shifted her focus into two competing thoughts that consumed her: how to have the most joy in her limited time remaining, and how to have a peaceful death.

Cathy had long told me that if it came to it, she was not interested in a protracted and painful death. We had some conversations about it, but I was never really sure how, when, or where she would try to die on her own terms.

One beautiful May morning, Cathy sent me a text that she was having a hard time, and that she was thinking of killing herself. I raced over to comfort her, and see if I could change her mind, but it was not to be. When I got there, she told me that she was ready to move on.

She told me that she was trying so hard to survive the cancer for me, and for us. But now that she was about to die, Cathy had no intention of waiting around for it to slowly kill her. She was tired of the pain and the hospitals.

We both said we loved each other, we hugged, and we cried. Cathy left the room and when I went to check on her, I found her outside, in her lounge chair, on the patio. She was slumped over and looked lifeless, but when I checked closely, I could tell she was still alive.

It was a horrible feeling knowing what she was trying to do, and also realizing it wasn’t working. I didn’t know what to do. I felt helpless and frightened. As I decided to call an ambulance and get her to the hospital, I felt like I had betrayed her final wish.

This was without a doubt the worst day of my life. It was heartbreaking, and I’m still horrified by it.

After regaining consciousness, she was spitting mad that she was alive and back in a hospital. We were counseled on various end-of-life care options and told Cathy would have likely been eligible for medical aid in dying, if only we lived in a state where it was authorized, like Vermont.

We were stunned and angered. How could there be such a compassionate option that would have significantly improved her quality of life – when she had so little time left – only to be cruelly denied access to it because of her zip code?

That was the precise moment we became advocates. We knew Cathy would not live to see it, but as it was her wish, I promised her I would follow through with my advocacy until it was done.

When first diagnosed, Cathy wanted to chronicle her journey through cancer in a blog that is still up at owmytongue.blogspot.com. It’s witty and inspirational. Read it, and you’ll fall in love with her like I did.

Shortly before she died, Cathy wrote: “I wake up each morning and catalog what’s failing on my body. What has deteriorated just a little bit more over the course of the night. Do you know how horrifying that is? Just sitting here feeling my body slowly destroy itself?”

She also explained her attempt to take her life: “Seriously, why did I try to kill myself? Because I hate having no control. My death is inevitable. I have a month or two at the most. So, since it’s inevitable, why can’t I go on my own terms? I would like to simply walk into my bedroom, lay down, and never get up again. It would be wonderous if it was that simple.”

It wasn’t. Cathy suffered grand mal seizures and lost consciousness. I was unable to care for her at home. It meant a trip to a hospice facility where she died three days later.

That is the verifiable harm taking place in the absence of medical aid in dying. People not only suffer terrible deaths against their wishes, but they also suffer the anticipation of it. Cathy was robbed of her ability to plan and make decisions about her death in the same way she did for her life. She was robbed of the freedom to make the most of her final weeks with the nagging thoughts of an uncertain death.

To honor Cathy and her strength, determination and sheer love of life, I will not rest until I keep my promise. Now is the time for state lawmakers to end the suffering for too many terminally ill New Yorkers and pass the Medical Aid in Dying Act.

Scott Barraco lives in Rochester.