Joe Biden’s Infrastructure Plan, New Orleans and the Ghost of Robert Moses

Moses 1946 Plan for New Orleans

When Joe Biden comes to New Orleans this week to pitch his $4 trillion infrastructure plan, he’ll have the unlikely ghost of Robert Moses trailing along. Though Moses role as “Master Builder” is synonymous with New York’s transportation system, his efforts to export his planning concepts to shape the urban environments in other US cities (for better and worse), including New Orleans, is relatively unknown.

If you’ve ever visited New Orleans’ French Quarter, devoured a beignet at Cafe du Monde, and strolled along the broad plaza of Jackson Square, you’ve no doubt marveled at an urban center whose core seems virtually intact from its boom years of the 1840s, when the city was the third largest in the United States. Jackson Square itself dates from 1721, when it was laid out by French colonialists (along with the rest of the Quarter) as the Place d’Armes, a military parade ground. Flanked by Spanish buildings dating from the 1790’s, the graceful St. Louis Cathedral from 1851 rises to look out over the Mississippi River, which originally fronted the edge of the Square, providing easy access for military and later commercial river traffic.

Though New York is the older city by a century, it’s New Orleans that wears the bones of its 18th century origins better than any other US city.

Robert Moses, of course, wanted to run an elevated highway right through it. Or at least along it.

In 1946, anxious to modernize the City and spur development of the adjacent central business district, City fathers (definitely no mothers were involved in this) hired Moses to lay out a highway system that would avoid the clogged streets of the 220 year old grid and facilitate the flow of traffic to the business district. (Moses took on similar projects for other cities including Hartford, Pittsburgh and Baltimore). The river had long ceased to be the sole conveyor of goods up the Mississippi, and the fading railways that replaced the river were to give way to a highway system capable of moving goods with the post war wave of truck traffic.

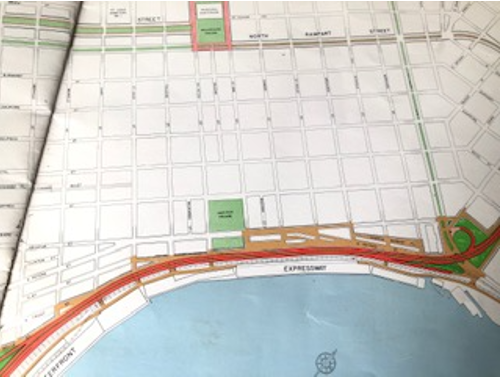

Moses proposed encircling the city with highways, much like his “belt” system in New York. The centerpiece was to be the Waterfront Expressway, an elevated highway slicing along the French Quarter directly in front of Jackson Square, yards away from Cafe du Monde. As in New York, with the West Side Highway and the East River Drive (now FDR Drive), the French Quarter would be cut off from the river that gave it birth. The 18th century heart of New Orleans, Moses argued, could best be preserved by encircling it with concrete and steel arteries.

The Moses Plan proposed a 60 foot elevated highway along historic heart of the French Quarter

Moses knew the objections to running a highway on top of the French Quarter and tried to disarm them in his report.

“There is no need to do violence to history or tradition in this process. It is only necessary to give sufficient attention to progress, or if you prefer, change, to prevent the Vieux Carre [Old Square] from becoming a sterile museum without vital associations with the the stream of life around it. Here the antiquarian and city planner must work together for the old and new.”

City officials, real estate developers and the business community were ecstatic about the Moses plan. But Moses himself wanted to keep out of the fray, and wrote into his contract that he would not be required to “attend functions, make speeches, or give interviews.” Moses stressed in the report itself that he had “no responsibility for persuasion or propaganda.” He was also not big on the idea that he would have to even actually have to come to New Orleans for the project, gaining as a condition of his employ that he would “personally…spend only so much time in and about the City of New Orleans as he shall deem necessary for…adequate supervision.” Indeed, there is no evidence that Moses spent any time in New Orleans, though he does appear to have dispatched the senior engineers of the Triborough Authority to the city.

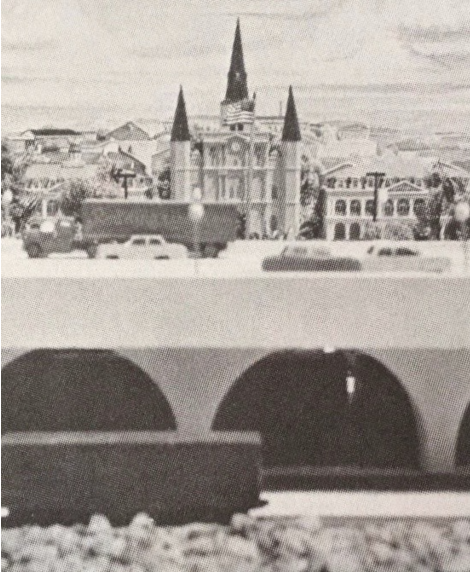

Model of Waterfont Expressway in Front of Jackson Square, a historic plaza dating from 1721. St. Louis Cathedral, rebuilt in 1851, rises behind

Moses plan came within a hairsbreadth of being realized. By 1964, what was now dubbed the “Vieux Carre Expressway” was formally designated as part of the Interstate Highway System, and the Johnson Administration approved funding in their final days in office. The growing preservationist movement took the battle over the expressway head on, spurring one of the nation’s most high profile battles to protect historic communities. The backlash against laying ribbons of highway through the middle of established neighborhoods shifted the politics of road building. In mid 1969, President Nixon’s new Transportation Secretary stunned local officials -who uniformly still supported the project- and canceled Moses expressway

Today, as you stand on steps overlooking Jackson Square (preferably sipping a Café au Lait), you can see the Mississippi River on one side and the 300 year old square on the other. You hear the horns of barge and tug traffic, train whistles, the clip-clop of horse and carriages, and the notes of street musicians lingering in the air in this extraordinary time machine of a city. What you won’t hear is the grinding and belching of tractor trailers that would have run across a towering two level highway on the very spot on which you stand.

President Nixon’s transportation secretary canceled the highway in 1969

Which brings us back to President Biden’s visit. While the French quarter expressway was shelved, another elevated highway -the Claiborne Expressway- running through the largely African American neighborhood of Treme just north of the Quarter, took its place. Before its construction, Claiborne Avenue was a broad, leafy boulevard lined with live oaks, the beating heart of that historic neighborhood. A diverse area dating from the 1820’s and populated primarily by free people of color (Black Creoles), the avenue became known as New Orlean’s “Black Main Street” as small businesses flourished along the corridor.

Robert Moses argued against building the Claiborne Expressway, acknowledging that the Claiborne would deprive residents of “needed light and air” and would have “a depressing effect on real estate.” He omitted the roadway from his report, seeing the Waterfront Expressway as the better alternative. Undeterred, city officials pressed ahead, adding it back to their plans in the late 50’s. Lacking the resources or the political power of their largely white neighbors to the south, the residents of Treme could not stop the expressway from being rammed through their neighborhood in the late 60’s, even as opposition to the French Quarter expressway was succeding. Today the area is characterized by the blight and despair that follows when bulldozers tear a hole through the center of a community.

Claiborne Ave before and after the Expressway

In recent years, there has been discussion in New Orleans about tearing down the expressway. In his infrastructure plan, Biden suggested that his goal was not just to rebuild and modernize existing highways, but to “unbuild” those that destroyed neighborhoods that lacked the power to protect themselves, specifically calling out the Claiborne in New Orleans and I-81 in Syracuse. “Too often,” reads the Biden plan, “past transportation investments divided communities – like the Claiborne Expressway in New Orleans or I-81 in Syracuse – or it left out the people most in need of affordable transportation options.” The plan sets aside $20 billion “for a new program that will reconnect neighborhoods cut off by historic investments.”

As Biden seems to understand, when Robert Moses opposed building a highway, it’s a pretty good sign it should never have been built in the first place.

Bonus Moses: Streetcar Edition

After you leave the French Quarter, visualizing the “Moses expressway that never was”, hop onto one of the streetcar lines, the historic transportation system that might have disappeared but for a little assist by Robert Moses. In the mid-1940’s, as Moses was drafting his highway plan for New Orleans, the death of the streetcar lines in American cities was well underway. (New York lost most of its 1300 miles of trolley tracks by the late thirties). New Orleans was not immune to the pressures of replacing streetcars, with their noise and lack of mobility, with buses. Moses went out of his way in the report to throw cold water on the idea. “We see no advantage to this scheme…New Orleans separate right of way which completely segregates street cars” was something to envy.

“Buses where no separate lanes are provided for them have a tendency to confuse traffic by weaving, stopping and doubling, and to pre-empt the curbs of ordinary streets. It is the vogue, no doubt stimulated by shrewd advertising and lobbying, to scrap all trolleys in favor of buses. New Orleans with its separate neutral ground [dividing median] would gain nothing by shifting from street cars to buses and giving up a unique and on the whole very successful local rapid transit trolley system.”

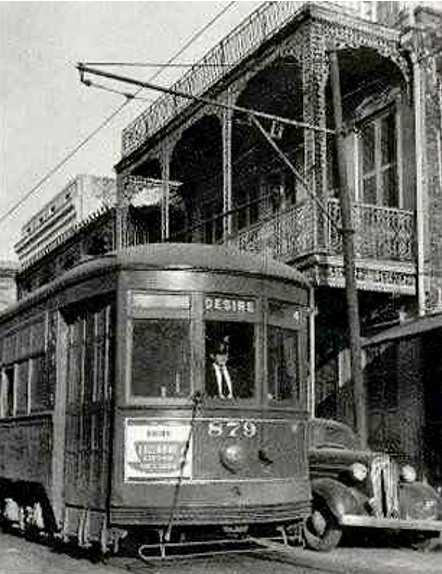

Moses voice was influential, but not enough to save the most celebrated trolley of all – the streetcar named Desire. As Moses was writing his 1946 report, Tennessee Williams was writing his famous play from the French Quarter, near a corner where the Desire line of the streetcar system ran. At the time, French Quarter residents sought to join the movement to replace streetcars with buses, thinking the trolleys too noisy and too “modern” for the French Quarter. The play was first performed in 1947, in New York, making “A Streetcar Named Desire” a household name and leading French Quarter residents to reconsider elimination of the suddenly famous line.

A streetcar named Desire

But once set down the track, municipal decisions are hard to brake, and a mere five months after the play’s debut, the actual streetcar line named Desire was dismantled and replaced by buses. Five streetcar lines still operate in New Orleans, including the oldest in the country along St. Charles Avenue, dating from 1835, each car operating on the line a designated historic landmark of its own. They are, as Moses said, “a unique and on the whole very successful local rapid transit trolley system”, one hundred and eighty-five years after the line opened.

The St. Charles streetcar line, operating since 1835.

Howard Glaser was the 2018 Theodore Kheel Fellow for Transportation Policy at the Roosevelt Institute for Public Policy at Hunter College, and has previously written about Robert Moses for Empire Report.