9-11 IS MORE THAN JUST A HISTORICAL DATE

For anyone college age or younger, Sept. 11, 2001 is yet another historical date they’ve learned over the years, like 1492 or Dec. 7, 1941. But for anyone who lived through the 9-11 terrorist attacks, it was nothing short of life altering.

As a reporter then covering the New York State Capitol for the New York Post, the attacks and the immediate aftermath was not only the biggest story I covered in a three-decade journalism career, but, needless to say, also the most emotional.

As we hit the 20th anniversary this Saturday, life has gone on. But I still vividly remember the horror, the sadness, and yes, even the absurdity of that time.

Waking up on the Tuesday of the attacks, my biggest goal for the day was to sneak out during lunch to buy Bob Dylan’s new album, “Love and Theft”, which was coming out that day. As I entered the state Capitol to start my day, I was walking up the three flights of stairs to my office with a Senate staffer when we passed the State Trooper desk in front of the Governor’s office.

“A plane just hit the World Trade Center,” he casually alerted us.

Thinking a small plane had accidentally clipped one of the buildings—not terrorism—I joked, “I guess I can go home. Not much news coming out of (the Capitol) today.”

By the time I made it to my office on the third floor and turned on the TV news, a second plane flew into the second tower. Not long after, I received a three-word email from my editor in New York City—our phone systems at headquarters were out.

“Go to Boston,” the email directed.

The two planes heading to Los Angeles that were hijacked and flown into the Twin Towers like two missiles had originated from Logan Airport.

I called my worried wife and told her I was on my way to Boston, roughly two-and-a-half hours away. I took off with no change of clothes, no toothbrush—and no idea what I was facing once I got there.

On the radio all hell was breaking loose, some true, some not so much. But at that time it was impossible to decipher. The first Tower collapsed. Then the second. There were reports a plane was on its way to the White House. That a car explosion occurred in front of the state Department in Washington.

As I made my way up the Mass Pike, I learned that then-Massachusetts Gov. Jane Swift was to hold a press conference in Springfield, Mass. I decided to go. Massachusetts does not appear to be a target, she said. Go about your regular business, she implored. It was primary day so she urged people to go vote. It was a reassuring message that would have been more so had she herself not been delivering it at what was basically an underground bunker.

Following her press conference, I arrived in Boston, setting up shop with the rest of the media at a hotel that overlooked Logan Airport. The first thing I did was head right to the airport. It was eerie. No planes were in the sky. The usually crowded airport was empty, except for investigators and a bunch of uniformed military personnel patrolling the terminal with heavy duty weaponry—a shocking sight I personally had never seen at that point on American soil.

I then headed to a hotel where many of the families of the passengers on American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175 had congregated. They weren’t allowing reporters in, but, wearing a Boston baseball cap, I managed to slip in, where I not surprisingly found worried and heartbroken family members hugging, crying and wondering what had just happened and whether there was a miracle chance their loved ones who had been on the plane were still alive.

After going back to my hotel and quickly filing my story, I decided to try and clear my head by going outside. It was a beautiful Tuesday. The sun was beginning to set. I was looking at the Charles River. And as bucolic a setting as it was, I felt nothing. I was absolutely numb, a feeling that would return for years—especially when looking up at a beautiful starry night sky.

The next day, I heard about a truly tragic story about a woman who had overcome a history of drug and alcohol abuse who was heading with her 4-year-old daughter and best friend to attend a spiritual conference at Deepak Chopra’s Center for Well Being in La Jolla, Calif. The group left a few days early because the woman wanted to surprise her daughter with a trip to Disneyland. The woman and her daughter had booked a flight on Delta that was shifted unexpectedly to United Airlines Flight 175. The woman’s friend was on American Airlines Flight 11.

Two friends, two different flights. Both ended up on planes hijacked by terrorists and flown into the Twin Towers. As their families told me their story, I did something I had never done during my journalism career before or after—I teared up.

I always prided myself for my ability to cover tough emotional or political stories without having it affect me. But 9-11 was different. For the most part, during the day when I was reporting, I was laser-focused. “Just do your job, ” I told myself more than once. But what happens when you are just inundated the entire day with the most horrific and heart-breaking situations, but are not processing it? It has to come out somewhere—and it did. I am not a cryer. My daughters tend to mock me for it. But during that week, I found myself every morning I was in Boston breaking down and sobbing for 10 to 15 minutes, almost like Holly Hunter’s character in “Broadcast News”. Only my breakdown wasn’t planned. But that emotional release made it possible for me to then go out and focus on my job.

One of the more bizarre moments that first week is when it was widely reported that the FBI had taken into custody a group of people staying at the Westin Hotel who may have been connected to the attacks. Later in the day, while having dinner with a colleague from the rival Daily News, it was reported the people taken into custody had been released. I suggested to my colleague that we go to the Westin and try to interview them about what happened.

When we arrived, we were met with a person in front of the hotel with a clipboard. He was only supposed to be letting people in who were staying at the hotel. “Your name,” he asked my colleague. “Joe Mahoney,” he said. The man looked down briefly at his clipboard, and said, “Okay” and let him pass. It was odd because neither Joe nor I were staying there, but I thought his name is not so uncommon, so.… Next it was turn. “Ken Lovett.” He again looked at the clipboard. He let me right in.

Joe and I roamed the halls but didn’t find what we were looking for. Before we left we decided to grab a drink at the bar. On the TV was wall-to-wall continuing coverage. The news channel cut to their reporter in front of the Westin where we were having our drinks who was recounting what had happened at the hotel. “Here at the Westin, security is tight,” the TV reporter said earnestly as Joe and I looked at each other in amazement.

By Friday, having not changed my clothes since I got dressed Tuesday, I was feeling pretty ripe. I ran to a nearby mall and bought some underwear, a pair of pants and a shirt. I also bought that Bob Dylan CD I had been so anticipating only a few days earlier. I put it on my car’s CD player, but it was too soon. I couldn’t get past the first minute of the first song.

By the end of the week, I headed back to the Albany area, where I live and reunited briefly with my wife. But on Monday, it was down to New York City, where I glumly covered a packed funeral at St. Patrick’s Cathedral of one of the 2,763 people who died at the World Trade Center.

Another day I was set to go to Ground Zero. This is a week after the attacks. “Be prepared,” a colleague who had already been there told me. “It’s a lot more devastating than it looks on TV.” “I don’t know, it looks pretty devastating on TV,” I thought. But boy was he right.

I arrived at the area near Ground Zero with no plan of how to get in. At this point, a week in, a number of celebrities had started to show up to encourage the rescue workers. As I walked toward the site, I encountered legendary boxing promoter Don King, dressed in a denim spangled jacket with his own face painted on the back. An officer ran up to him and excitedly asked King to talk to his girlfriend, which he did. I then got an interview with the self-promoting promoter who in 90-seconds managed to express outrage at the terrorist attacks, admiration for the rescue workers—and promote an upcoming fight. As legendary New York Post columnist Cindy Adams says, “Only in New York, kids.”

An officer eventually let me into the site. As I walked around, I realized my colleague was right. TV did not do the destruction justice. There was still smoke coming up from the ground. A burned-out piece of one of the Towers that was still standing gave it the feel of Roman ruins. You could see through one destroyed building right into another. Put simply, it looked like someone had dropped bombs in a war zone. The smell could drop you to your knees. Even to this day, if I pass by certain fires, usually a bad electrical fire, the smell takes me right back to Ground Zero.

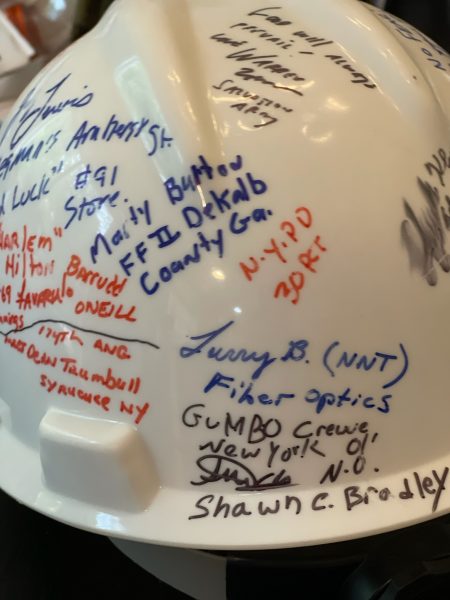

But there was something else. Rescue workers and other volunteers looking for survivors or bodies. Right outside Ground Zero, a group of men from Louisiana who dubbed themselves the “Gumbo crew” were serving up the homemade stew to rescue workers and volunteers for free. One of the men told me they were home watching the coverage when they saw a rescue worker eating a fast-food hamburger. “That’s not right,” they said to themselves. They quickly cooked up two big vats of gumbo, loaded it on their truck and drove non-stop to New York City to do their part.

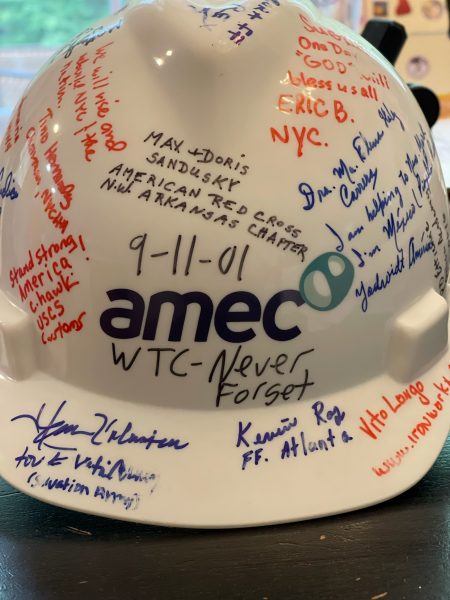

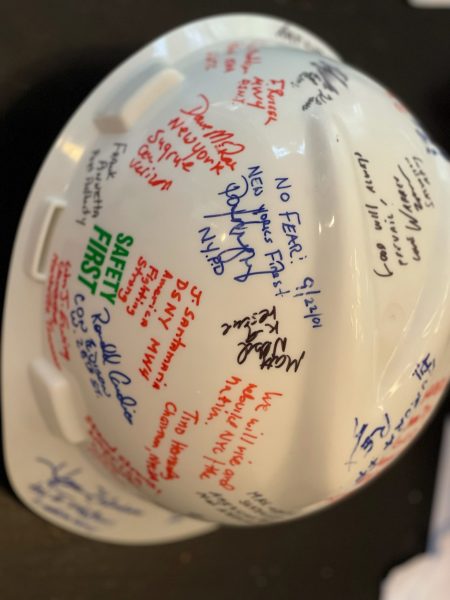

Even in the face of such horror, humanity prevails, I thought. That got me thinking. The next night, when I was off, I went back downtown to the site, carrying the pristine white hardhat a worker had given me when I was there the day before. I stood outside one of the entrances into Ground Zero, not as a reporter but in admiration. As rescue workers came out, I did something I never did in my career: I asked for autographs, that they sign my hardhat. I told them: “I’ve interviewed presidents, governors, ballplayers, actors and musicians, and I’ve never asked for an autograph. But what you are all doing here is absolutely incredible. And years from now when I’m telling my kids about 9-11, I want to have some tale of hope that came out of it to give them. What I’m seeing here is that.”

These were everyday people doing heroic work. And they happily signed. Some wrote messages, like “Good will always prevail,” “Stand Strong America,” “No Fear” and “We will rise and rebuild NYC/the nation.” Some just signed their names. But the helmet was filled—and, yes, I show it to my kids when we talk about 9-11 as a sign that even in the face of unthinkable evil and tragedy, the goodness of the human spirit prevails and remains an inspiration. That is the lesson I prefer to focus on even two decades later, knowing that for so many, Sept. 11, 2001, will always be more than just another date students hear about in history class.

Lovett was an award-winning reporter for 30 years, including 25 covering the New York Capitol.