Breaking the Cycle: Rethinking Violence in Our Communities

Decades ago, my college professor introduced us to functionalist theory, which posits that every aspect of society, even its negative elements like crime and violence, plays a role in maintaining social stability. This theory aims to explain how social structures work together to sustain order, but it raises unsettling questions when applied to marginalized communities, particularly in communities of color.

In these communities, gun violence is not merely a statistic; it’s a daily reality. Many young people grow up in environments where violence is a constant threat. This violence is both a symptom and a tool of broader social structures designed to perpetuate inequality and struggle.

Functionalist theory suggests that various social structures, including education, the economy, and even crime, work together to maintain societal balance. But what happens when this balance is inherently unjust? In communities of color in NYC, cycles of being under resourced and disenfranchised are reflections of a system that benefits keeping certain groups marginalized. The violence is not just a breakdown of social order; it’s a grim aspect of its maintenance.

Media portrayals exacerbate this issue by reinforcing stereotypes. The algorithm often glorifies violence and aggression turning real-life into a form of entertainment. For many young people in impacted communities, gangs offer a sense of belonging and respect that society frequently denies.

The comfortability of violence in media and music distorts real-life. Diss tracks between artists might end with better record sales. In contrast, the “diss tracks” between gang members often end in bloodshed. This stark contrast highlights how violence has become normalized.

Why do so many young people in NYC seem to lack a love for life? When violence is pervasive in everyday life, it desensitizes individuals to its severity and it’s difficult for young people to not choose that route.

Some may argue that these outcomes are failures of the city system of affordable housing, unequitable healthcare and educational investments. Even some elected officials who preach moderate change or progressive agendas continue to represent the cycles of repetition. But what if they are, in fact, the system functioning as intended? When communities are systematically deprived of a better quality of life, they are set up to fail. By limiting exposure to broader opportunities, we effectively place ceilings on potential.

My professor illustrated his point using the example of crime and punishment. He asked us to consider what would happen if crime were eliminated. What would become of our police, our lawyers, judges, courts and funeral homes? What would become of our news, which thrives on stories of tragedy more than on stories of hope?” His question underscored a disturbing truth: crime, poverty and its consequences are deeply embedded in our social and economic systems. If we built up all aspects of our communities what would be lost? The question—are we truly committed to ending crime and poverty, or are we merely managing it in a way that maintains social equilibrium?

My recent conversation with a well-respected public school principal further illuminated the issue. Her insights were both simple and groundbreaking. She observed that society provides certain communities with just enough to keep them afloat but never enough to thrive. How can we expect the next aerospace engineer or heart surgeon to come from certain neighborhoods in New York City if we only expose them to constructed ceiling that is their community. Her insight reveals a fundamental issue: when we limit resources and opportunities, we limit the future for community especially children.

It’s a cruel irony that we expect miracles from communities systematically deprived of hope. We have created environments where the extremes of the moral compass play out in real-life aggression and violence.

Gun violence should be viewed as both a mental health issue and an epidemic. The trauma inflicted on communities where violence is normalized is profound and psychological. Exposure to violence can lead to collective PTSD, affecting entire communities. Young people, still developing mentally and emotionally, are particularly vulnerable.

To tackle gun violence effectively, we must address the underlying trauma driving young people to violence. It’s not just about removing guns—it’s about equipping young people with healthier coping mechanisms.

Addressing gun violence requires systemic change and intentional investment. We must challenge the structures that maintain inequality and work to provide real opportunities and resources to those who could be left behind. We need to invest in positively expanding cultural narratives that shape perceptions and behaviors.

We need broader societal change that offers young people a future beyond their immediate environment—a future where they can dream of becoming something out of their ordinary.

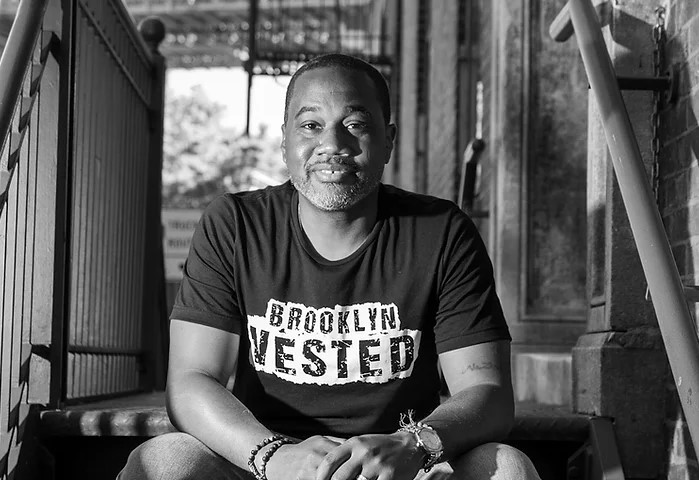

Khari Edwards is a candidate for Brooklyn Borough President.