Analyzing Complex Public Policy Issues

The Step Two Policy Project recently posted a 10,000-word Policy Brief on A Review of the Managed Long-Term Care Issues in the FY 25 Executive Budget, which includes an in-depth analysis of a legislative proposal to eliminate partial capitation managed long-term care (MLTC) plans and return to a fee-for-service reimbursement system for managing home and personal care. This proposal, which has been introduced in both the Senate and the Assembly, is called the Home Care Savings & Reinvestment Act. It is not included in the FY 25 Executive Budget but is being advanced by important stakeholders as an alternative to other long-term care cuts proposed in the Executive Budget.

This Commentary is not intended to be a summary of the analysis in our Policy Brief. Rather, I want to use the analysis of this proposal as an example to describe the process of analyzing complex public policy issues. One of the core principles of the Step Two Policy Project is that democratization of analysis of important public policy challenges can be useful to policymakers by providing objective, fact-based analyses of complex issues so they can make more informed, better decisions. This Commentary describes our analytic process.

The process of analyzing public policy issues involves three basic steps: developing the “theory of the case;” articulating a strawman proposal[1] that operationalizes the theory of the case; and a bottom-up empirical analysis of the strawman proposal based on the available data and transparent assumptions.

The theory of the case should be as specific, and its logical premises as explicit, as possible. When examining the legislative proposal to eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans, we started by trying to understand the underlying logic of the policy decision to require mandatory enrollment in managed long-term care, which was recommended as part of a broader “Care Management for All” policy adopted by the first Medicaid Redesign Team (i.e., MRT I) in 2011.

There was a clear rationale for the Care Management for All policy. In short, the theory of the case then was that managed care would be more capable than the fee-for-service system in serving vulnerable individuals with complex needs, which in turn would result in cost containment as well as better individual outcomes. The rationale was based on a series of assumptions, namely that MLTC plans would:

- Have the authority and autonomy to manage care for its members across the full continuum of settings, customizing care plans in a way that was more generous (in terms of allocated hours of care) to some of their members and less generous to others in order to maximize outcomes while controlling costs

- Ensure a sufficient supply of provider services and hold providers accountable for quality, outcomes, and costs, while in turn being accountable to the State on these matters; and

- Operate in organizational structures that created financial alignment with Medicare plans (as the payer for medical services) so that financial incentives would exist to use long-term services and supports (including those addressing social determinants of health) to reduce the overall total cost of care including medical care.

For reasons that we describe in our Policy Brief (see p. 4-7) the actual experience with partial capitation MLTC plans has been pretty much the opposite of the original intentions of the Care Management for All philosophy.

So, what is our theory of the case with respect to the proposal to eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans and return those members to fee-for-service plans? Our theory of the case rests on the following premises:

- First, that the actual implementation of Care Management for All policy in the form of the partial capitation MLTC plans so bastardized the original vision that few, if any, of the expected benefits are being realized;

- Second, that the State could develop a program based on the fee-for-service reimbursement system that would produce the same or better programmatic outcomes as partial capitation MLTC plans at a materially lower cost to the State; and

- Third, that elimination of partial capitation MLTC plans would also serve as a catalyst to enrollment in fully capitated MLTC plans because partial capitation MLTC plans would seek to shift their members to their affiliated full capitation MLTC products, which at least achieve the financial alignment goals of Care Management for All. Increasing enrollment in full capitation MLTC plans has been an important strategic priority of the State for a number of years, but participation cannot be mandated, and enrollment in such plans is still only about 19% of the number of enrollees in partial capitation MLTC plans.

The second step in the analytic process is to develop a strawman proposal that operationalizes the theory of the case. Our strawman proposal is as follows:

- Eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans following an 18-24 month implementation period;

- Retain full capitation MLTC plans such as PACE and Medicaid Advantage Plus as an alternative for enrollees who wanted to remain in a managed care plan;

- Expand the scope and improve the performance of the recently created Statewide Assessor so that it would have sufficient autonomy and authority to develop effective and efficient person-centered plans of care (i.e., “care management” as opposed to “care coordination”);

- Ensure high-quality “care coordination” services by requiring the State to contract with care coordination organizations which (unlike Health Homes) would have a direct contractual relationship with the State in order to to improve accountability; and

- Manage payment and other administrative responsibilities through the State or its contracted vendors without any involvement from the Counties to ensure alignment of financial interests.

In developing both the theory of the case and the strawman proposal, it is important to consider alternative points of view that are in the mix. There are now at least four alternative policy viewpoints on this issue that need to be understood and considered:

- The 25 partial capitation MLTC plans and certain stakeholders that are part of the current ecosystem are opposed to the FY 25 Executive Budget proposal to allow the State to procure MLTC plans and are vehemently opposed to the legislature’s proposal to eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans and return all members to fee-for-service reimbursement except for those who enroll in fully capitated plans such as PACE and MAP. A group called the MLTC Coalition[2] has issued a White Paper and Fiscal Impact Analysis that argues, that the partial capitation MLTC plans have been a success, suggesting that elimination of these plans would increase annual costs by between $3.0 billion-$4.5 billion.

- The administration, as reflected in the FY 25 Executive Budget proposals, implicitly believes that many of the problems with partial capitation MLTC plans would be solved through procurement of MLTC plans, which would enable the State to improve the program by only working through plans that met the State’s quality and efficiency metrics. The arguments in favor of procurement of managed care plans in general, including partial capitation MLTC plans, are set forth in DOH’s Final Report on Managed Care Organization Services.[3]

- The advocates for elimination of partial capitation MLTC plans (led by 1199SEIU) implicitly are suggesting that because the programmatic and fiscal failures of these plans – irrespective of whether they were inherent in the original design or resulted from the failures in implementation – are so comprehensive that the State should start over from scratch with the fee-for-service system at its core. The Home Care Savings & Reinvestment Act reflects the position of advocates for eliminating capitation MLTC plans.

- The principal architect of the Care Management for All policy in 2011 believes that the current system is fundamentally broken, but believes the solution is to fix the system by reversing decisions made during implementation that undermined so many of the core principles of the policy of mandatory enrollment in managed long-term care.

We are not making a recommendation with respect to the proposal to eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans at this time because the State may have additional information that changes our conclusion. That said, our theory of the case and strawman proposal are more consistent with that of the advocates than any of the other viewpoints articulated above.

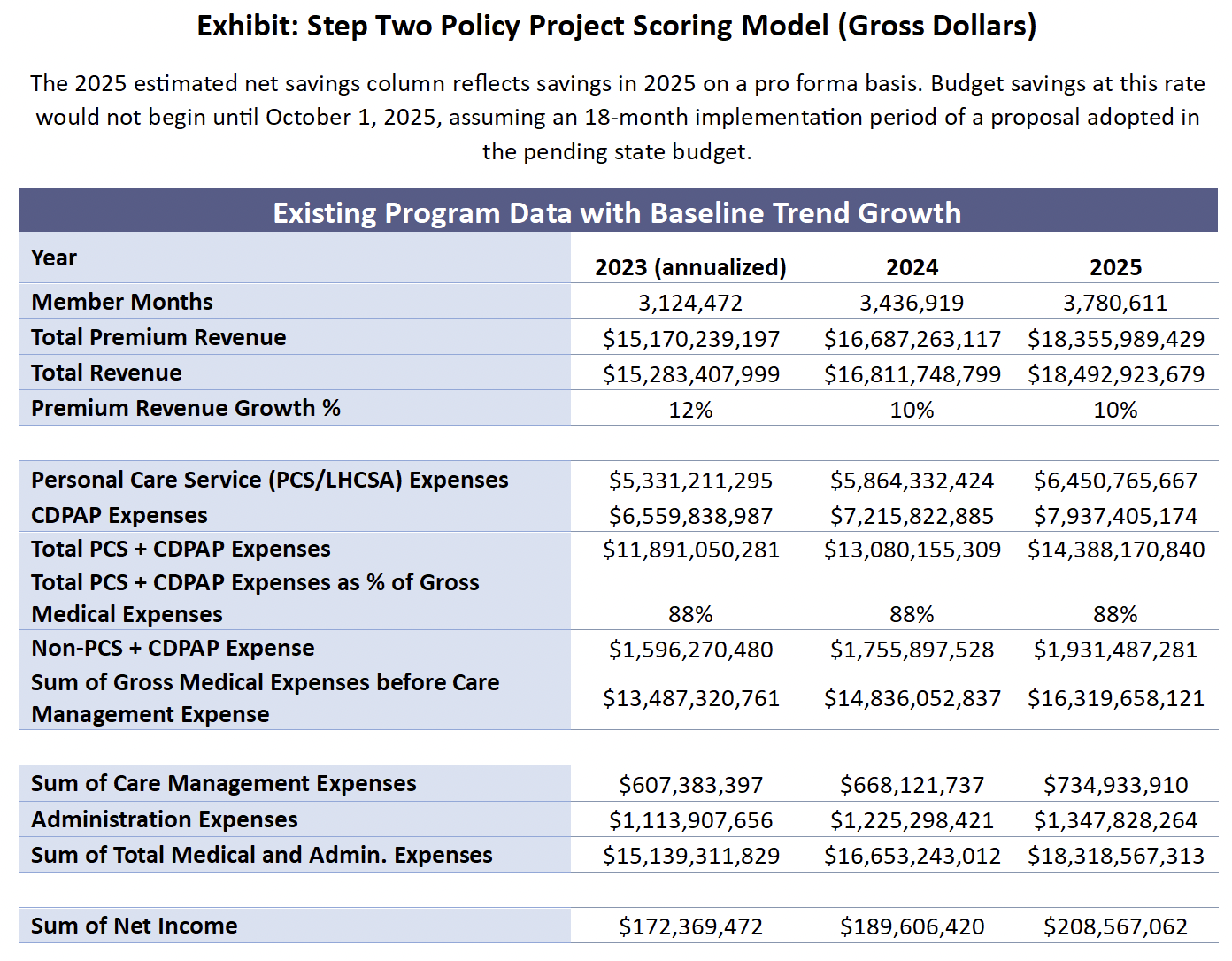

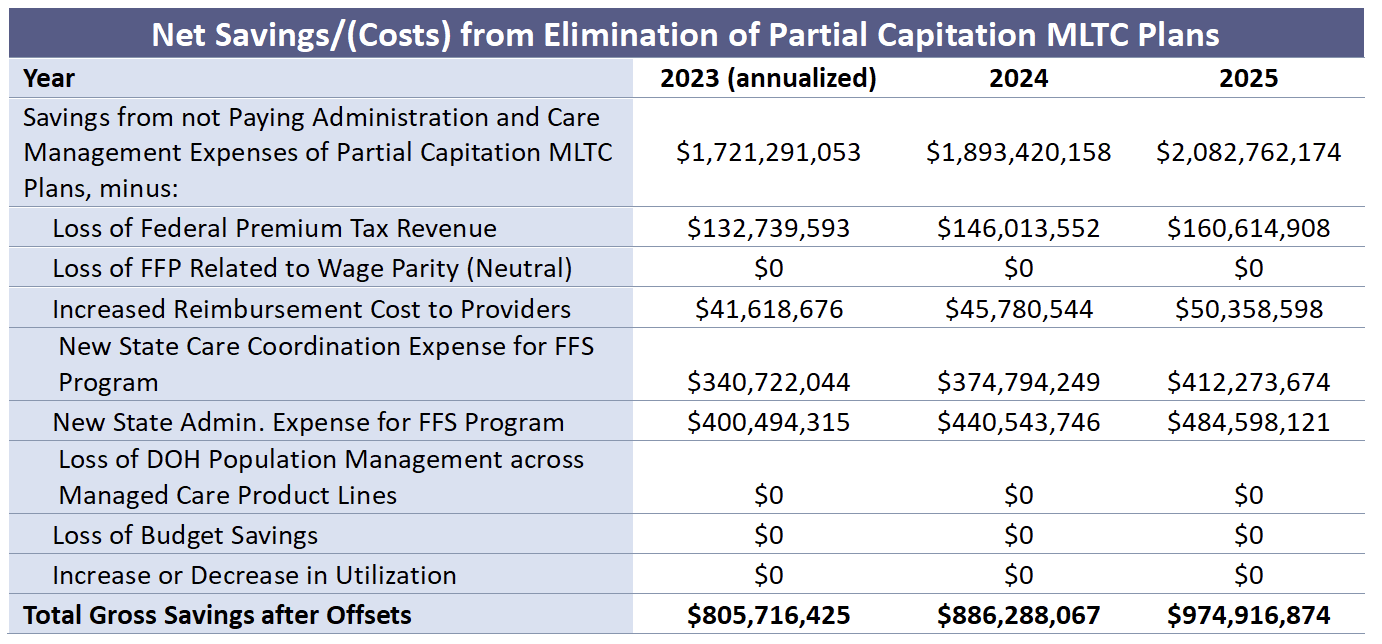

The third step in the process of analyzing a complex public policy issue is a bottom-up and data-driven empirical analysis of the strawman proposal that is supported by transparent assumptions on which the analysis relies. In budget-making terms, this third step of the process is called “scoring” the proposal. Scoring requires the identification of the relevant data and assumptions that are most likely to reflect the actual experience if the proposal were adopted.

I like to think of the scoring process as “thinking in spreadsheets.” It starts with identifying, and having access to, relevant data. In the case of this proposal, cost reports submitted to the State by the partial capitation MLTC plans provide the most relevant data (i.e., plan revenue, enrollment, service costs paid to providers, care management expenses, and administrative expenses). Although this data is publicly available, it requires some serious data crunching to make the information accessible. The “thinking” part of the scoring exercise involves the determination of assumptions, which are levers that are designed to demonstrate the impact of different aspects of the strawman proposal. Ideally, these assumptions should be anchored in objective benchmarks.

The scoring process should also take into account differing assumptions and any variations in data put forward by others who are analyzing the proposal in question. Both the advocates and the opponents of the proposal to eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans have made available to policymakers their own data-driven and empirical analysis of the proposal.[4] In addition, the administration will need to score the Home Care Savings & Reinvestment Act if it is included by either the Senate or the Assembly in their One-House budget bills.

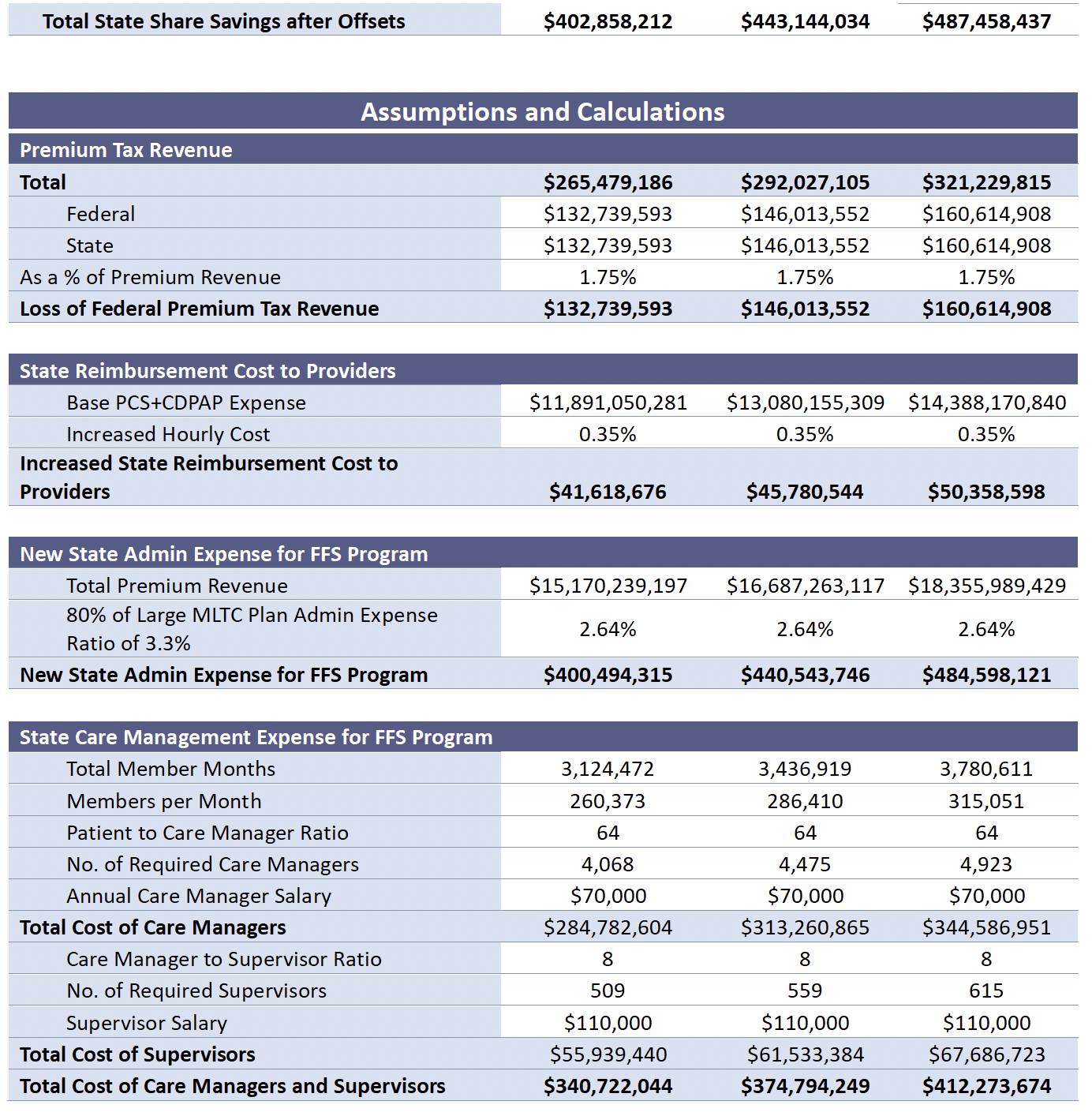

Different analyses may use different objective benchmarks for anchoring their assumptions. For example, the 1199SEIU analysis bases its estimate of the cost of care management/care coordination on the per beneficiary cost of providing this service through Health Homes in Washington state. By contrast, both we and the MLTC Coalition analysis built up the cost of providing this service based on the number of care managers, the ratio of supervisors to care managers, and the annual compensation expected for each.

Although both we and the MLTC Coalition used the same construct to estimate the cost of providing care management/care coordination services, we employed different assumptions by using different objective benchmarks. The MLTC Coalition developed its estimate of the cost of developing alternative care management services on the assumption of a care manager to patient ratio of 1:40 and a supervisor to care manager ratio of 1:5. The source for these benchmarks is described in a footnote in the MLTC Coalition White Paper as “Health Home Standards and Requirements for Health Homes, Care Management Agencies, and Managed Care Organizations.”[5] However, in reviewing that document, it appears that these ratios apply to health homes serving children, which is likely to be a more complicated process than maintaining individuals in personal care for extended periods of time. The devil is always in the details.

Our scoring of the alternative cost of care management assumes a care manager to patient ratio of 1:64, which is the required ratio in the Basic Health Home program and a supervisor to care manager ratio of 1:8. Our assumptions could be refined based on more granular information about the population enrolled in MLTC plans and a survey of the actual care manager to member and supervisor to care manager ratios in the partial capitation MLTC plans. But the nature of scoring often requires making assumptions based on incomplete information.

In some cases, different analyses will disagree not only about which piece of benchmark data should be relied on but also whether objective benchmarks exist on which to anchor assumptions. For example, the MLTC Coalition uses a statement made by the DOH actuary in 2015 that MLTC rates would be 33% below fee-for-service costs in order to make their estimates of increased utilization of between 5% and 16% seem reasonable. Our view, however, is that the 2015 comment by the DOH actuary is not a valid benchmark on which to anchor the assumption and that the MLTC coalition’s scoring range is simply a hypothetical estimate.

We don’t think there is an objective benchmark on which to base an assumption regarding changes in utilization. As a result, we essentially rely on our theory of the case – which is that partial capitation MLTC plans lack the motivation or tools to control utilization – to conclude that utilization would not increase if partial capitation MLTC plans were eliminated.[6]

We are attaching our scoring model as an exhibit in this Commentary. The model identifies our assumptions for trend growth in the data and the basis of each operating assumption made in the model. The Policy Brief explains our reasoning behind our assumptions, starting on p. 16.

We consider our scoring model here to be a good “back of the envelope” estimate of the fiscal impact of the proposal to eliminate MLTC plans. With more data and more time to consider different potential benchmarks for assumptions, a more robust scoring model could be developed. In my experience, however, these back of the envelope models tend to be pretty close to the results found when the data is sliced and diced more finely. The back of the envelope model also has the advantage of making it easier to find the forest for the trees than can be the case with a scoring exercise that seeks to model every possible variable.

As noted above, one of the Step Two Policy Project’s reasons for being is our belief that decisions regarding important, complex, and controversial issues – for which the proposal to eliminate partial capitation MLTC plans certainly qualifies – benefit from the analysis by objective third parties as part of a transparent public policy debate. We hope our Policy Brief on this topic, which followed the analytical process described in this Commentary, can contribute to this debate.

Paul Francis serves as Chairman of the Step Two Policy Project.

_________________

[1] I am using the term “strawman proposal” here to mean “a brainstormed simple draft proposal intended to generate discussion of its disadvantages and to spur the generation of new and better proposals” (Wikipedia). This is not to be confused with a “strawman argument”, which is “the distortion of someone else’s argument (instead of addressing the actual argument) to make it easier to attack” (Scribber.co.uk).

[2] The coalition is composed of MLTC plans and certain stakeholders, including the New York Conference of Blue Cross and Blue Shield Plans, the New York Health Plan Association, the Home Care Association of New York State, LeadingAge New York, and the New York State Coalition of Managed Long Term Care Plans.

[3] It should be noted that while elimination of MLTC plans and procurement of MLTC plans are mutually exclusive, the other programmatic savings proposals in the FY 25 Executive Budget (such as those involving CDPAP) are payer agnostic and thus could be adopted with or without changes that directly impact MLTC plans.

[4] The analysis of the MLTC Coalition opposing the proposal has been made public and can be found here. The analysis of those advocating for the proposal was developed by 1199SEIU and its consultants. Their analysis, which we understand is being revised based on feedback they have received, has not been made public but has been shared with policymakers and made available to us at our request.

[5] MLTC Coalition White Paper, p. 11.

[6] Without articulating the basis for its conclusion, the 1199SEIU analysis similarly assumed that there would be no increase in utilization if the proposal were adopted.