COVID-19’s negative impact on child mental health

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a host of short-term and long-term impacts. One of the least explored is the negative effect on the development of our children.

Over the past two years, school-aged children have suffered potentially traumatic events – known clinically as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) – that threaten not just their educational achievement, but also their social and emotional development in a way we won’t fully understand for years to come.

The issue is particularly fraught for children – especially those who face homelessness – who have not only had to deal with fear of the virus and its impact on their families, but also disruptions to their everyday lives. Whether dealing with housing instability, accessing tools for virtual learning for a year, teachers and friends out sick when in-person school resumed, having to wear masks and maintain social distance at school, students have had to manage ever-evolving challenges. Outside of the classroom, there have been other disruptive changes to their routines—cancelled extracurricular activities, missed birthday parties and sleepovers with friends, not seeing grandparents and other family members, and for some, housing and food insecurity to name just a few. For many kids, these issues left them feeling socially isolated and suffering from anxiety and depression that often accompanies such isolation.

An advisory from the U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy last year warned “the pandemic era’s unfathomable number of deaths, pervasive sense of fear, economic instability, and forced physical distancing from loved ones, friends, and communities have exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced.” Murthy cited recent research covering 80,000 youth globally that found depressive and anxiety symptoms doubled during the pandemic, with 25% of youth experiencing depressive symptoms and 20% experiencing anxiety symptoms.

The impact was not equally felt. According to the Surgeon General, it’s estimated that as of June 2021, more than 140,000 children in the US had lost a parent or grandparent caregiver to COVID-19, with Black youths more likely to have suffered such losses. Latino children reported higher rates of loneliness and poor or decreased mental health as a result.

Making matters far worse is the intersection between health care inequities and economic stress experienced by parents. For example, a Kaiser Family Foundation national study found that twice as many Black and Latinx parents than white parents expressed concern about missing work to take their child to get vaccinated or care for them if they have side effects. The study also found that a significantly higher number of Black and Latinx parents have concerns about getting a vaccine for their children from a place they trust, as well as fears over the difficulty of traveling to a vaccination site.

If we are to address the current crisis and its impact on children, different segments of the community—government, schools, the health care system, businesses, and parents – must work together to develop wholistic and inclusive solutions. We need to encourage better community engagement by, and collaboration between, these sectors, while also increasing funding and access to mental health services.

It is all interdependent. The connection between the physical and mental health of children is tied directly to a thriving economy and the economic circumstances of their parents. Homeless children as a group are particularly vulnerable to ACEs. We must prioritize the intersection of poverty and mental health, and see housing stability as a critical, intergenerational component to mental wellbeing.

There are things we can do now to mitigate the impact of ACEs due to COVID, such as keeping kids in school safely to continue their educational, emotional, and cognitive development while also promoting positive peer interactions.

Businesses can do better by providing family leave accommodations, so parents don’t have to choose between staying home to care for their children or keeping their paychecks.

In New York, Governor Kathy Hochul recognized the impact the pandemic has had on small businesses and proposed up to $250 million small business tax credit to cover COVID expenses. This funding should include covering the cost of workers who need to stay home to care for their children, alleviating a major stressor for lower income workers. The Governor also has proposed spending $2 billion for pandemic initiatives that she and the state Legislature will decide how to spend in the upcoming budget negotiations. Some of those funds could go toward both adult and child mental health services related to COVID, particularly for those who are often harder to reach due to homelessness.

Schools should be more aggressive in monitoring the mental health of its students, while states should provide the funding for needed mental health services, like school psychologists. Youth-serving community organizations and houses of faith must also play their part in addressing the mental health of our young people through community health programs.

In times of crisis, studies have shown kids tend to be resilient in the face of adversity. The impact of COVID-19 however poses what can only be viewed as a once in a lifetime ACE, for which we have no comparable data. With many young people feeling like they are losing their childhoods—and literally losing family members and friends—the impact of COVID-19 on their mental wellbeing won’t be known for years to come. As we move to mitigate the impact, with increased attention and engagement across sectors of society, we must help children develop attributes that support their resiliency in adjusting to their current circumstance and alleviate the continued threats of the pandemic on their development.

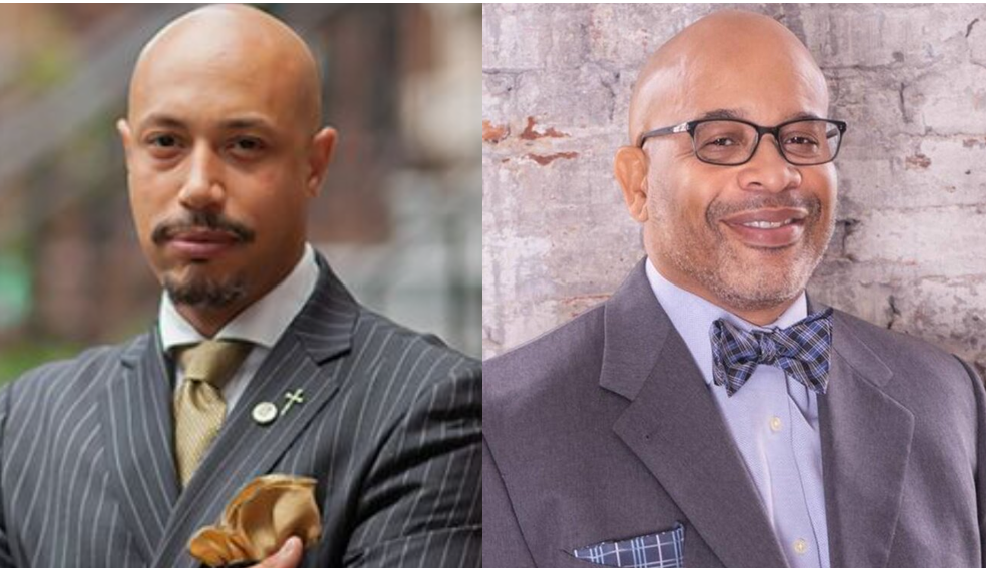

Elder Kirsten John Foy, President and CEO of The Arc of Justice, is a civil and human rights leader mobilizing communities across the country.

Le’Roy Reese, Ph.D. is a pediatric clinical psychologist. He is an associate professor at Morehouse School of Medicine in the Department and Psychiatry and serves as a senior advisor in the healthcare practice at Ichor Strategies.